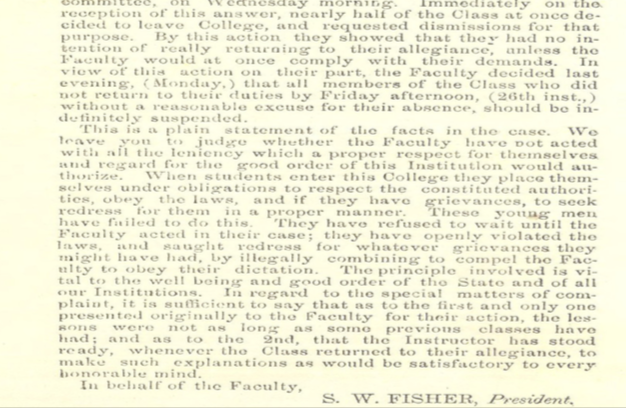

The faculty make their ending remarks concerning the behavior of the junior class. Photo courtesy of Hamilton College Archives.

“Into the Hamilton College Archives” is a new recurring column that seeks to explore the often forgotten texts and artifacts in the Hamilton Archives. The Archive holds both Hamilton and Kirkland College records of enduring value from administrators, faculty, students and alumni from the founding of the Hamilton-Oneida Academy to the present. Each article in this column will introduce one or two items from the collection, offer background information and occasionally consider their possible current implications. At times, some of the items chosen from the archives will shine light on the everyday, social aspects of life on the Hill; other times, they might complicate your beliefs about the College’s history. Regardless of the effect, I hope this column will teach you a little bit more about the College’s past!

This week, I will focus on an amusing letter written by College President Samuel Ware Fisher on behalf of the faculty. The letter, dated June 23, 1863, opens with the following excerpt:

“On Tuesday, early in the afternoon, a committee from the [Junior] class waited on the President, and requested to have their lessons in German shortened. They stated that their instructor in that department had at their request shortened the lesson for a single time, and then lengthened it; and that he refused to entertain the request to shorten it again. The President informed them that the Instructor was the proper person to judge the average ability of the class to get a lesson, but that he would converse with him on the subject as soon as it was convenient. He accordingly sought an interview with the Tutor, but did not find him in time to have the result mentioned to the committee before the afternoon recitation. The great majority of the class, without waiting for a response to their request, refused to go into the recitation, many of them assembling at the door of the recitation room and acting in a most disorderly manner. They thus assumed the attitude of resistance to the legitimate authority of the College, and determined to dictate to the Instructor what lessons they would and what they would not learn.”

The rest of the letter details the Junior class causing further disruptions and assuming “open and combined rebellion against the College authority.” Though their initial reason for creating disturbances appears petty, the juniors ultimately found the instructor’s uncivil treatment of them as a personal matter which they believed justified their actions. As punishment, two of the juniors were suspended while the rest were given a warning. The faculty did this to “make an example of a few and thus endeavor to save the many.” Instead of ceasing their disobedience after witnessing the punishment of their peers, many juniors instead refused to do their work. However, by next Monday, the class had signed a paper stating that they would return to following the rules on two conditions: the faculty acknowledge the improper conduct of their German instructor and that they allow the two suspended students to make their case. In response, the faculty said that they were not in a position to meet with the class as a whole but would meet them through a committee; hearing this, half the Junior class left the school and requested to be dismissed. The faculty decided that if the students did not return by Friday, they would be indefinitely suspended.

This unusual scenario appears amusing and perhaps a little ridiculous given that a professor’s refusal to shorten a German lesson resulted in almost half of the junior class leaving the college and engaging in disruptive behavior. However, there might be more than mere antics behind the class behavior. Taking place in the summer of 1863, this event occurred in the middle of the Civil War. Though the College was physically separated from the actual battlefield, the students might have felt the rebellious and fighting spirit present throughout the nation. What would these students have thought and felt in the relative safety of Hamilton College knowing that the country was in the midst of its bloodiest conflict? This instance of rebellion is only one example of the many acts of protests undertaken by Hamilton students; more organized (and perhaps more noble) acts of protests against the Vietnam War and divestment from South Africa would occur in the next century and a half after this peculiar incident.

The junior students were also more affronted by their professor’s lack of respect and the miscommunication between them and the faculty. Tensions between students and faculty (or the larger administration) is a common enough occurrence though not to this extent. There exists a power imbalance between students — who pay tuition and a variety of other fees but are subordinated to respect their professors — and the faculty whose livelihood depends on their employment but also must take up the role of superiors. Today, the divide between professor and student is not as wide or as hostile as it was in 1863, but the power dynamics are still interesting enough to ponder. This one letter may seem like an amusing text at first but it reveals the legitimate antagonistic relationship between students and superiors and reflects the mounting chaos of the time. If you found this brief glimpse into the College’s history interesting, I will tackle the students’ response letter in the next submission of “Into the Hamilton College Archives.”