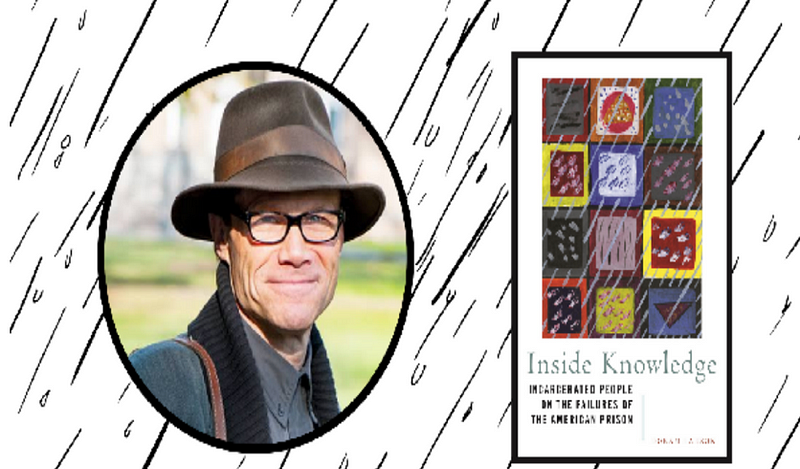

Professor Doran Larson, from the Literature department, published Inside Knowl-

edge in which he explores mass incarceration through prisoner testimonies this month. Photo courtesy of Skylight Brooks.

Professor Doran Larson recently published, Inside Knowledge, evaluating the American prison system through prisoner testimonies. Larson uses prisoners’ testimonies from the American Prison Writing Archive to

argue that mass incarceration further harms prisoners and their families rather than rehabilitates them.

Larson contends: “What do we need to do for this person in order for them to be incorporated back into society in a constructive and legal way. We are really backwards looking.”

The unfortunate reality of our current system is that “It is about punishment. It is about vengeance. Also it’s about sustaining one of the largest employment sectors in the country because the system has gotten so large.”

Larson begins Inside Knowledge by providing a history of the prison system in America. He includes testimonies to “demonstrate through the eyes and testimonies of incarcerated people how the prison does not only achieve its four cardinal rationale for being, but actively defeats them.” In chapter two, he argues that prison actually “defeats meaningful retribution,” furthering his argument by emphasizing the “complete lack of or action counter to rehabilitation.”

Larson believes that containment is not always the best solution for deterring crime. There are harmful residual effects on families from “taking someone out of the community who may be a household breadwinner, legally or not,” Larson asserts.

Larson’s final chapter focuses on how America’s current prison system fails to provide prisoners necessary support post-incarcera-

tion. This support is integral to keeping people out of prison.

Larson emphasizes that prisoners’ maintenance of long term personal relationships following their sentence is crucial to keeping them out of prison. However, these relationships are difficult to foster when you are locked up and isolated for a concerted portion of your life. He also believes “integration into the community” deters people from crime post-incarceration, but carrying a felony record further isolates people who have been incarcerated from their communities. A felony record also prevents people from getting higher level job positions.

While prison systems vary state by state, Larson was surprised to find striking similarities between the testimonies. “Even though there are about six thousand legal detainment facilities, people in those facilities cannot really communicate with each other, sometimes by state regulation and sometimes by law. Nonetheless the writing that comes out

of those institutions reads as if it came from one place,” said Larson. This demonstrates America’s prison system has collective values and incentives, entrenched in systematic racism and exploitation.

Larson commented on prisoners’ selflessness: “The other thing is the enormous generosity and courage of incarcerated people because these are institutions that don’t want this information to get out. And there is no such thing as private property in prison and people can get themselves in trouble by writing non-fiction about their experience. And nonetheless they are willing to do it. What I mean by generosity is that it is rare that you read essays in the archive in which the author is really focused entirely on themselves. They are really talking about systemic issues and they are writing for other incarcerated people. They understand themselves as representatives for tens of thousands of people who will never write about the experience.”

Larson believes true prison reform can only be achieved if the numbers are substantially reduced. “If you can imagine a prison that actually does rehabilitative work, you can’t really do that when you still have the numbers of people inside. When the numbers go up, you are just managing that population. You can reduce violence but you can’t really move farther to positive directions just with the number of people in there. Just reducing the numbers is crucially important.”

Larson was inspired by his own experience working in the prison system and doing past research inspired Inside Knowledge. “It grew out of running a writing workshop at Attica Correctional facility for ten years,”Larson explained.

Larson explained the academic projects that inspired Inside Knowledge. “With a research assistant in 2009, I wanted to put together basically a textbook of non-fiction writing by currently incarcerated people in order to teach in an undergraduate class at Hamilton. There was no such book, so we essentially put that book together. It’s called Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America consisting of 71 essays from 27 states. But after the deadline for that book passed, the essays just kept coming. With the grant from Mellon Foundation, we created American Prison Writing Archive which is where most of the work in Inside Knowledge comes from.”

Larson published an academic book on Irish, African and American prison writing but continued on to write Inside Knowledge because he “wanted to write a book that could be more widely read for a popular audience.” Larson and his colleagues have other volumes planned, however Larson thought this introductory book was important “simply to

deflate the myths simply about you know the positive constructive things that prisons do.”

Larson’s book uses prisoners’ personal stories to illuminate the injustices of mass incarceration and give voice to prisoners experiences.