This February was an eventful Black History Month.

We saw cases of high-ranking government officials donning blackface, Jussie Smollett’s dramatic, planned attack, and racially-inappropriate clothing designed and sold by Gucci — just to mention a few instances of racially-sparked news. It seems that every single day was plagued by some sort of racial issue or scandal. An overlooked issue was Michael Cohen testifying against President Donald Trump towards the end of the month. Cohen accused Trump of being a racist, a conman, and a cheat. The examples of racism he proceeded to give were interesting.

For example, Cohen claimed that Trump challenged him to “name a country run by a black person that [is] not a shit-hole.” I am black and from Kenya. None of the 46 countries in sub-Saharan Africa currently have a white president. The last one was Guy Scott, an acting president for Zambia between October 2014 and January 2015, and he was the first since F.W. de Klerk, South Africa’s last apartheid-era president, left office in 1994. It is true that most of our countries are not as developed as Western countries, but we are on the road there.

The problem with the common “underdevelopment” stereotypes is that they are a result of stories portrayed by the mass media that are either not entirely true or blatant falsehoods. Last semester, I watched a TED Talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a prolific Nigerian author, who says it is the danger of a single story that fails to paint the true picture of Africa. It does not surprise me when people question whether Africa has cities, or if it is just a desert, or if its people have electricity. Honestly, it is not their fault. Having grown up flooded with images of Africa as a war-torn, dry, and desert-like area, who can blame them?

Another startling moment from Cohen’s testimony was when Congressman Mark Meadows, a noted supporter of President Trump, brought forth a black woman, Lynne Patton, as proof that the president is not racist — simply because she is employed in the Trump Administration. The logic is flawed whichever way you look at it. First of all, the act of bringing a black woman in to show that you are not racist is derogatory, as she is reduced to some sort of prop or measure for racism. Also, in keeping with that logic, a married man can defend himself against claims of sexism by virtue of being married to a woman; or, if my next-door neighbor is of a different race, I am automatically disqualified from being racist. Secondly, bringing Patton in to show that the president is not racist sparked a whole debate about who is racist and who is not, which really shows how spectacularly narrow the race discussions are in our current society.

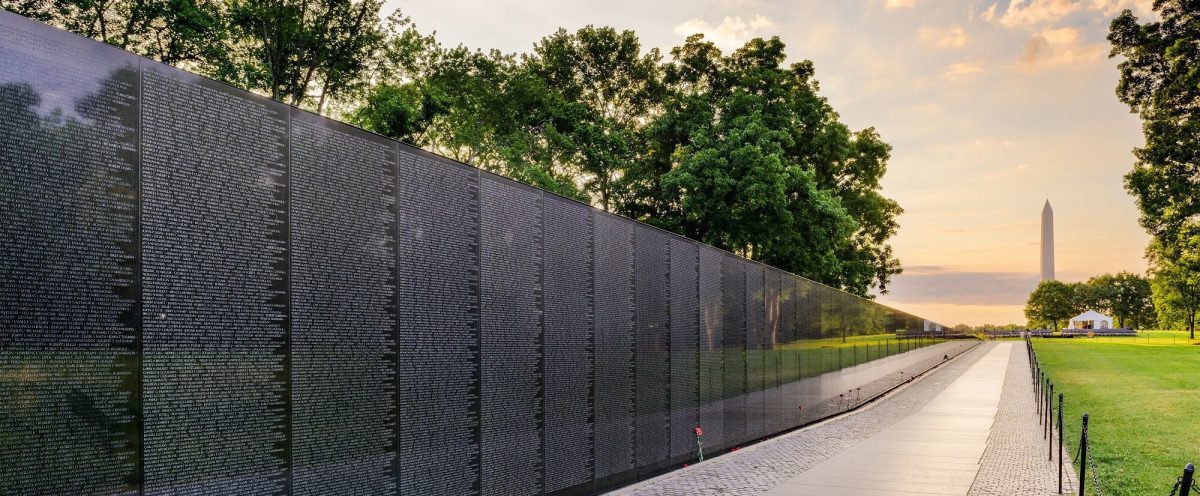

A possible reason why race discussions are so narrow has to do with how history is taught in America. As Trevor Noah says in his book,

Born a Crime

(a wonderful read), history is taught, largely, through facts, which often negates the important moral and emotional dimensions of the past. Compare that to Germany, for example, where children do not finish high school without learning about the Holocaust — the hows and whys, its gravity and legacy. They grow up with a sense of accountability.

In an ideal world, a socially-constructed idea like race would be a nonexistent concept. After all, we are all the same beneath the skin. Yet in a world that insists race does not matter, racial issues almost always end up making the headlines. If there is hope for a better future, the discussions toward race have to change and empathy must take the place of our judgmental human tendencies.

‘From Where I Sit’ is a column dedicated to the voices of students enrolled in ESOL classes. If you are interested in contributing a piece, contact Features editors at [email protected].