There was a time when 11 a.m. on a Thursday meant something. Those aware of this time know that this is a reference to streetwear juggernaut Supreme’s weekly drop schedule. This was an era of culture more so than what many consider to be fashion. I say this because there was a blatant disregard for the style of the clothes in exchange for the social connotation that wearing them would bring. Minimalist script-logo t-shirt that can match with pretty much any outfit… no thank you. Hyper-niche deliberately ironic anorak tracksuit with former President Barack Obama’s face plastered all over it? I may wear it once for the meme, but the social clout is indefinite.

Between the hypebeast era of the mid-2010s and the uniformity of workwear and nondescript brands like Carhartt that dominate today’s moodboard-driven monoculture, there is an identifiable bridge that connects these two seemingly disparate junctions in one’s fashion self-realization. There is a life-span concentric circle showing the progression of fashion incited by the hypebeast era.

During the aforementioned hypebeast era, teenagers and older-skewing Zoomers began to define the zeitgeist while millennials controlled the production of it. In the mid-2010s, these Zoomers (and I speak from personal experience) were often transitioning from a time in their adolescence where social currency went from worthless to valuable. These children grew up playing sports or listening to music in the era of signature sneakers (i.e. Kobes, LeBrons) and brand-patented attire (i.e. Nike Dri-Fit) that epitomized capitalistic attraction toward the idealistic identities (i.e. celebrities and professional athletes) that were associated with the clothes that they were wearing. Mix this with gaudy merch for franchises or music acts that were found in mallfront stalwarts like Hot Topic and Zumiez, and the eventual integration into the overt style of hypebeast streetwear makes sense. In the model of the concentric circle, these actors expanded the intended scope of reception to their social projection from essentially just close peers to a broader audience. This coincides with a natural coming-of-age where the schools these kids go to often get bigger, more diverse and social interests start to increase beyond the trivial fun of sports and recreational play to establish oneself in the social life that they inhabit on a 24/7 basis.

The niche became mainstream and the mainstream became obsolete when the hypebeast era approached. Gone were the days of wearing athletic shorts and hoodies acquired during family trips (shout-out all the deserted Hershey hoodies); enter skinny jeans and Vans. The turn to streetwear for many in this era was an attempt to look cooler and older but not age out too quickly. Collared shirts and slacks were still too formal, but joggers and Champion hoodies hit a sweet-spot of personal growth. Streetwear occupied a space that exhibited this same personal growth but also created a binary dichotomy of self-proclaimed trendsetters and ‘culture-vultures.’ Brands like Supreme and Palace were still largely associated with the skating culture that birthed them during the hypebeast era’s genesis and so those making a 180-degree pivot from Nike-Elite socks and LeBron 14s to Supreme-Hanes socks and checkered vans were often met by close-friends with pause and others with accusations of appropriation. Rather than taking time to reflect on one’s own style, the hypebeast business structure of the instant social gratification of its clothes mixed with a controlled leadup to each release squeezed the decision-making process for children who wanted to quickly infiltrate a new social level within the concentric circle. The rapid-fire succession of clothing and sneaker releases, all substantially hyped during this period, forced the hands of those who wanted to invest in what they saw as a rising stock: both the actual resale value for the products for future riddance and the social value. For those who could not afford box-logos or Bape shark-hoodies, small accessories like underwear or tank-tops with minimal-but-overt-enough branding to project their knowledge of the culture without being able to fully buy in.

The appeal of the hypebeast era was exacerbated by celebrities who were young enough to have wanted sought-after streetwear with the current means to finally afford it and flaunt it relentlessly. Pivotal pop-culture moments rippled across the youth, such as the XXL 2016 Freshman Cypher, where Lil Yachty donned an Jordan Brand x Supreme hoodie. No media conglomerate was more influential in this era as Complex. From their Sneaker Shopping installments to their Closets series, celebrities who were teetering on mainstream notoriety like Tyga and DJ Khaled vaulted into the zeitgeist with their exorbitant expenditures. And effectively into the hearts and minds of mini-hypebeasts everywhere.

Growing out of the hypebeast phase of walking billboards is a yearning to blend into the masses. Young adulthood often entails college, entering new social networks and a further broadening of one’s audience. Workwear brands like Carharrt and Dickies provide refuge to those who have started to care more about fits than pieces. Supreme and Bape pieces are difficult to insert into certain outfits with their high flamboyance and wacky graphics, in addition to how their tonality does not fit all settings the same way understated workwear can. You would not wear a Supreme work-shirt filled with ironic obscenities to class or a menial job the same way you could wear a solid-colored Dickies one. There is still room for youthful exuberance and streetwear in this part of the life cycle; brands like Stüssy and Dime offer a mix of timeless pieces that would likely not be designed by a fast-fashion entity but are not so outlandish as to be definitely a branded item rather designed by a fast-fashion entity but are not so outlandish as to be definitely a branded item rather than passing as a standard article of clothing.

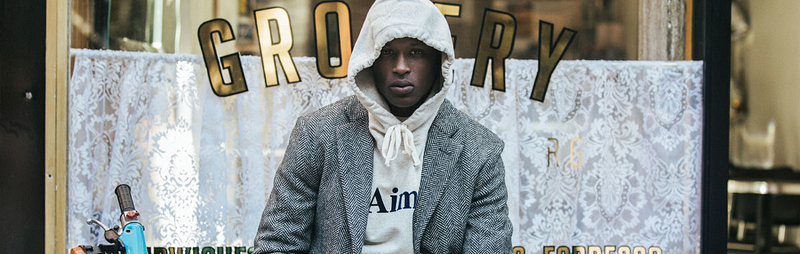

You are now getting older, probably near the end of your educational career, and are entering the white-collar workforce with aspirations of dressing up beyond your means to physically showcase what status class you aspire to be a member of. Brands like Aimé Leon Dore and Noah allow you to cosplay as old-money when you are really just trying to get some new money. They ooze a mature sense of financial freedom that the aforementioned brands seem disconnected to in their naivety. What ALD and Noah do is dress up streetwear to the extent that it blurs the lines of what that designation truly is. Instead of a $45 fleece beanie, you now wear an $85 one that is crocheted and shows your refined taste.

All experiments eventually reach their conclusion, and a lot of the time, people want to return to the comfort of their earlier wardrobes but just update it for contemporary times. J. Crew and Abercrombie & Fitch have rebranded toward this audience accordingly, providing cost-efficient alternatives to essentially high-fashion streetwear like ALD. More than this though, there is an accessibility and tactile aspect to this phase. First branding mattered, then the aesthetic of the entire outfit did and now how it physically dresses is of the utmost importance, and the masses of physical storefronts for brands like J. Crew and A&F provide extra security to the return on investment that buying new clothes should guarantee at this point in one’s life.

The concentric circle model is more appropriate for these patterns of life than a chronological timeline plot because in the latter, you cannot go back in time. But in the concentric circle, as in life, you can traverse inward and outward of the model as you see fit. Fashion, culture and personal taste is not static and no one should ever feel stuck in one of the phases that I have explained.