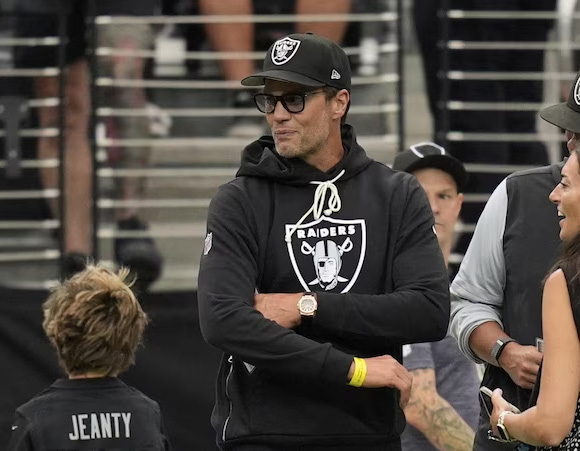

The Last Dance

follows the career and journey of basketball star Michael Jordan while playing for the 1997–98 Chicago Bulls. Photo courtesy of ESPN.

Three years ago,

The Last Dance

was released on Netflix. It was a seminal moment for sports documentaries; aided by the lack of sports on the calendar due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it took center stage in the sports world telling the story of the 1997–1998 Chicago Bulls, Michael Jordan’s final championship team. Since then, I feel like we have been getting a lot of copycats that have been damaging the medium and preventing good projects from getting off the ground. So how did we get here? And how can we make sports documentaries good again?

The last few months have seen a significant outpouring of sports documentaries, particularly on Netflix. Over the summer we had

Untold: Johnny Football

and

Untold: Swamp Kings

, which discuss the fall of Johnny Manziel’s football career and Urban Meyer’s tenure at Florida, respectively.

Beckham

, a four part series about the career and off the field fame of English midfielder David Beckham, followed in the fall. All three docuseries follow a familiar format: an ex-athlete telling their story, a few contemporaries give background details and stock footage of past games fill in the rest. The problem is that this repeated format does not create a good documentary. There is no discovery. It is just a highlight reel. The subjects themselves are the draw-in factor, which is the problem. To get the involvement of the athlete, athletes become producers. As a result, the documentaries do not have any bite to them. Untold:

Johnny Football

barely mentioned Manziel’s alleged domestic violence against his ex-girlfriend in 2016.

Untold: Swamp Kings

glosses over Aaron Hernandez’s murder conviction. If these documentaries are not going to tell the real story, why do they keep getting made?

All of these sport documentaries have one goal in common: they want to be

The Last Dance

, a retelling of history through the mouths of those involved. Everyone is trying to make the lightning strike twice. Except that is not going to happen — it cannot happen.

The Last Dance

was a one of one and there is no way to recreate its context.

It was successful because it presented Jordan as a powerhouse — a basketball savant fueled only by his desire to win for better or worse. This was not the young Jordan who dazzled, smiling as he sold you McDonalds and Gatorade. He was the talented veteran with an ego to match; Jordan had a reputation for pettiness and was known to fight with his teammates. Director Jason Hehir dove deeply into how being atop the mountain changes a man. The team behind the project had a wealth of footage to feature. Before the 1997–98 season, Jordan and the Bulls agreed to give a film crew constant access for the full season. The catch was that any use of the footage had to go through #23. For years, Jordan refused, until something changed.

In June 2016, Jordan gave Hehir’s team the green light. After years of pitches from the likes of Spike Lee and Amblin Entertainment’s Frank Marshall, Jordan finally decided it was time to tell his story. What happened just that month that might have convinced the long-skeptical Jordan to participate in such a project? LeBron James won his third Larry O’Brien Championship Trophy after defeating the Warriors, challenging Jordan’s status as consensus greatest basketball player of all time.

Jordan’s story is another reminder of why we need change in the industry. These are not works of history or journalism as a proper documentary should be. They are ammunition shells in fandom wars. If you are a Michael Jordan fan,

The Last Dance

is your scripture. Whenever we get the inevitable LeBron James retrospective career docuseries, it too will be little more than a brand extension. Lebron already has a production company in Springhill Entertainment and has employed a film crew to follow him much like the Bulls did in 1997–1998. There is an understanding of what these films can do from a marketing angle. Beckham himself said that watching

The Last Dance

inspired him to create this most recent project. It also came in the wake of criticism for his work as an ambassador to the controversial Qatar World Cup. So long as these ulterior motives exist, sports documentaries will continue to live in the shadow of what came before them.

The Last Dance

was great but it was the last time you can tell that kind of story in that way.

Sports documentaries need to go small. The push to cover these bigger stories brings with it the baggage of partners and their politics. The more seats at the table, the less everyone gets to speak. Take

Hoop Dreams

, a documentary from 1994 about two Chicago highschoolers trying to make it into the NBA. It examines the impoverished conditions that produce world class American players. The documentary was incredibly successful in its day, in part because it had to stand on its own merits. There was no pre-existing fanbase to tap into. Going smaller means that filmmakers will have the freedom to tell their stories. But there is a risk, of course, as having the face of a famous athlete certainly beats a random unknown. Still, it has to be worth a chance.