Watching a film by directed Kamal Al-Sheikh (1919–2004) invites a reflection on human behavior. Al-Sheikh was the kind of director who liked to rely on subtle gestures to convey significant meanings. The simple yet evocative visual composition of his films reveals a profound contemplation of human interaction.

Al-Sheikh’s cinema is the farthest from what the Egyptian audience expected or had been used to. The Egyptian film industry started with the production of musical film that was more concerned with featuring talented musicians and singers. The intended meanings in these films were explicitly stated rather than conveyed through stylistic methods. It was not foreseen to have films that dealt with the subtlety of human psychology. The lightness of the musical, which albeit demonstrated decent levels of production and other technical aspects, contrasts with the depth of the psychological interrogation in Al-Sheikh’s films.

While there was not a sudden transition from musical film to Al-Sheikh’s cinema, the intended meaning of these films were not always understood or appreciated by the audience. From a cultural perspective, it was not in the nature of the Egyptian people to exercise psychological analysis. An intellectually autonomous man, Al-Sheikh took to criticizing socio-political issues, such as the influence of war on society, through revealing their contemptible reflections on human behavior.

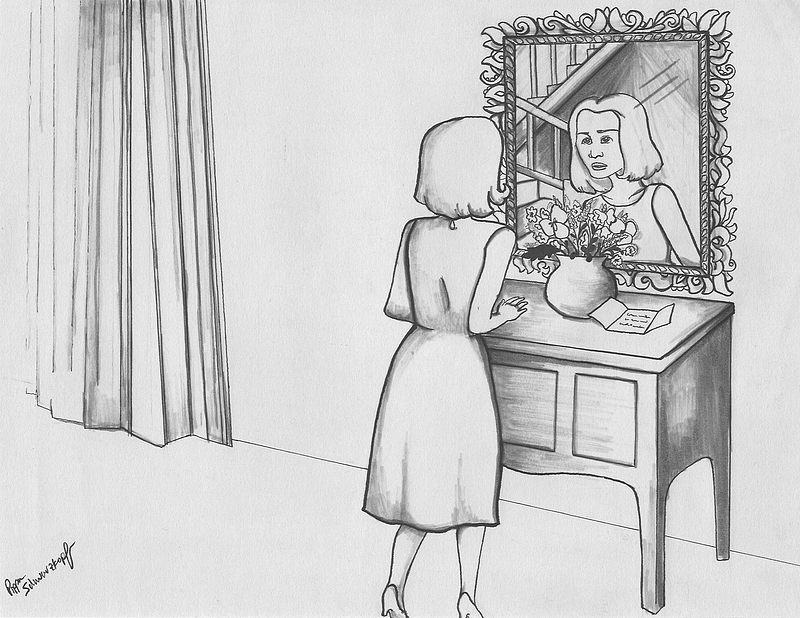

In his film

The Last Night

(1963), a middle-aged woman suffers from amnesia and, in an atmosphere of distrust, does not know who to believe when it comes to the truth about her real identity. Her last memory is of a Second World War air raid in 1942. In one shot, she looks at her reflection in a mirror with bulky decor that reduces her reflection. With a 15-year gap between the present moment and her last memory, she is both overwhelmed by and in denial of the vagueness of her identity. The loss of memory corresponds to the irrevocable transformation of social identity that is caused by war. Al-Sheikh demonstrates the weight of this taxing transformation as tangible on an individual as well as a social level.

With an artistic approach that is fundamentally different from that of other directors of the period, Al-Sheikh stands out in the history of Egyptian cinema. Unlike other directors, who illustrated emotion through setting or employed actors’ expressive performances in a realist framework to convey socio-political criticism, Al-Sheikh was mostly interested in humanizing his characters. The differences between the personalities of the characters provide the audience with different perspectives of the other characters, helping the audience see them in different lights.

Another Al-Sheikh film,

I Won’t Confess

(1961), centers around the moral dilemma of Fathi, a young man who, unintentionally, involves his brother-in-law in a theft, but feels reluctant to own up to his share of responsibility. Al-Sheikh portrays Fathi as be immersed in his own indulgences, not stopping to see the damage his deeds have caused to his family. However, he has a close relationship with his nephew, a young boy who is the son of Fathi’s brother-in-law. Their interaction has more of a friendly than authoritative feel. Fathi’s

sister, the mother of the young boy, is confused, as she does not believe that her husband acted unethically and feels obliged to protect him. In a sense, her hesitation mirrors her brother’s complicity in the theft, they both experience a moral dilemma. Fathi ends up turning himself in, but he is not portrayed as a criminal as much as a person who made a mistake and decided to own up to it. Toward the end of the film, the nephew is shown holding a toy rifle that evokes the playfulness of his uncle’s character and their relationship. The fact that Fathi made a mistake does not ultimately exclude him from the family.

Al-Sheikh’s stylistic choices demonstrate his emphasis on humanizing the featured characters. The minimal reliance on makeup gives each actor’s visage a sense of transparency. There is no barrier between audience and actor; instead, it is direct human communication. The shots are not framed by certain objects in the scene, giving them an open feel as well as a sense of depth into the world of the film. In Al-Sheikh’s mind, framing a scene might have created an undesirable artificiality of the shots which he did not want, especially given his emphasis on conveying the psychological mood of the characters and of the atmosphere in which they find themselves. These choices provide the lens through which Al-Sheikh wanted the audience to see his characters.

This contemplative gaze that Al-Sheikh devised is not limited to the “fictional” characters in his films; it inspires a certain way of looking at somebody in an objective light.

This writing project is supported by the Kirkland Endowment Fund.