On Monday, April 2nd, Dr. Sarah Pralle was invited to speak at the College. Dr. Pralle is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School whose research centers on environmental advocacy and policy. Her talk was entitled “The Politics of Flood Mapping and its Implications for Climate Change Adaptation.” It was hosted by the Environmental Studies Program and the Government and Geoscience Departments.

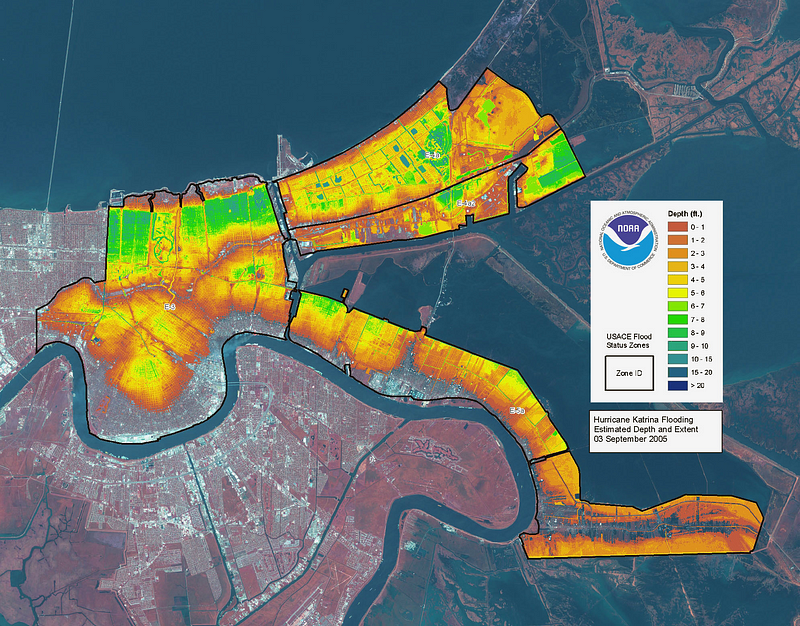

Dr. Pralle began with the realization that flood mapping is flawed. When FEMA began a remapping process pursuant to the National Flood Management Program in 2000, there was a generalized consensus that existing maps were not accurate. However, now the accuracy of the new maps is being questioned. The five basic problems are as follows.

First, flood maps, as they currently exist, are misleading because they suggest that risk is an “in or out phenomena,” rather than a spectrum of risk. They lead us to believe that if you are in a flood zone area, you are at risk, whereas if you exist outside of the region’s border, you are not at risk. This gives people a false sense of security because risk is a continuous variable, and the only people who are really risk-free are those who live, say, on the top of a mountain.

Second, flood maps falsely assume that areas behind levies are not at risk for flooding and therefore these areas do not appear on maps. However, this magnifies risk because people can make decisions to live in these areas, thinking that they are immune from any risk of flooding, and then experience this calamity without even knowing it was a possibility. It is important to remember that levies can fail, especially if they are not maintained; therefore areas behind levies should not be excluded from flood mapping.

Third, maps seem to suggest that the amount of risk for all properties within a given designation is the same, when this is not the case. I One house may be flooded three inches, and another home may be flooded three feet. Moreover, houses in lower income areas are more vulnerable than more affluent one because of a lack of resources. Thus, even if both neighborhoods have the same flood risk designation, the magnitude of the risk both experience is not the same after considering this social, or resource-based, vulnerability.

Fourth, the flood maps that are currently used for regulatory or insurance purposes don’t indicate future risk. Flood risk is calculated using reflections of past and present risk. At best, these maps indicate the current risk of flooding, which is not especially helpful in an age of climate change. Essentially, these diagrams are reflecting static predictions in a changing world, which is of little use to homeowners.

Finally, these maps might not even reflect the best current predictions of flood risk. Although FEMA is supposed to redo the maps every 5 years, often times the date on the map changes but the actual map reuses the same data. This may occur when the paper copy of the map is digitized, for example. Or, a small part of a much larger region may be remapped, and the map will still be considered “updated.”

These five realizations lead to the larger conclusion that mapping is not an objective or purely technical process, but instead involves political decisions that affect how risk is calculated and displayed. Homeowners, particularly in middle and lower class communities, tend to be opposed to having their regions remapped. This is because the main use of flood mapping is for insurance purposes. If citizens’ homes are remapped within a flood zone, whereas before they were not, they will now have to pay premiums, which are generally about 700 dollars a year. For many families, this is simply not an affordable option. Moreover, being mapped into a flood zone may make it harder to resell a property, placing homeowners in a double bind. They cannot simply abandon their homes without sacrificing the equity they have built up, but they must also deal with added costs. As such, citizens tend to petition local and state legislators to reduce or postpone the remapping process. Politicians are generally inclined to meet these requests because historically, legislators who have fought to reduce the flood zone have gained favor with both their communities and the media, boosting their reelection prospects.

Dr. Pralle argues that while political engineering on the part of citizens and legislators might be a legitimate short term solution to help homeowners avoid unaffordable or unwanted costs, it will not work in the long term. Not only does the current status quo favor more affluent communities, whose greater access to resources makes them more able to fight the remapping process; but, in the event that these unmapped areas do flood — and they will with increasing frequency, due to climate change — homeowners who need bailouts but have not purchased insurance will have to pay out of pocket, or rely on whatever federal emergency funds will be allotted to them. This is not a sustainable long term solution.

Moreover, premiums will go up as the size of the floodplain is reduced and less people will be required to buy insurance, creating an increased financial burden for those people who are still at risk for flooding.

Instead, Dr. Pralle argues that a more tenable and ethical long term solution would be creating an insurance program that covers all kinds of disasters that everyone would buy into. This would include not just flooding, but droughts and heat waves, winter storms, tropical cyclones, wildfires, and severe local storms. It would ensure that people from all parts of the nation would benefit — even if you don’t live in a flood prone area, it would still be in your interest to buy in because it may offer other protections that you can foresee yourself as needing, such as wildfire protection.

Moreover, mandating that everyone buy into it would make premiums go down, making the program more affordable for all.

In a world of ever-changing climatic conditions, such a program might be the contingency plan that homeowners nationwide will need to adapt to the changing world, and it might succeed in doing so in a way that reduces the inequities of the current model.