On Thurs., Apr. 17, students, faculty and staff gathered to hear about the new administration’s economic policies, risks for the American economy and current market sentiment from a former economist at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors at a time of economic uncertainty and market volatility.

Held in the Fillius Events Barn, Professor of Economics and the Henry Platt Bristol Professor of Public Policy Ann Owen gave a presentation called “Tariffs, Inflation, and Prospects for the US Economy.” Owen shared her perspective on the short-run effects of President Donald Trump’s economic policies on inflation, labor markets and GDP growth, as well as the long-run impacts on institutional quality, innovation and the importance of independent monetary policy.

Owen began the presentation by prefacing that “we only observe the economy after it happens, so I cannot tell you what is going to happen in the future. What I can tell you is what people are expecting to happen in the future.”

“What we should keep in mind as you think about what people are expecting to happen in the future is that economic expectations are often self-fulfilling,” she noted.

Turning to tariffs, Owen said that “it is a little difficult to think about what the goal of our current tariff policy is, because it seems like the goal is not always the same.”

On Apr. 2, Trump declared that foreign trade and economic practices have created a national emergency, and imposed a 10% tariff on all countries to take effect Apr. 5. “President Trump will impose an individualized reciprocal higher tariff on the countries with which the United States has the largest trade deficits,” a statement from The White House said.

Trump’s tariff policy, as outlined in the White House statement, has three main goals: taking back economic sovereignty, reprioritizing U.S. manufacturing and addressing trade imbalances. The administration argues that unfair trade practices have harmed American workers and industries and created a dependence on foreign suppliers. Trump highlights the disparity in tariff rates and non-tariff barriers faced by U.S. exporters in countries like China, India and the EU, arguing that reciprocal trade will improve U.S. competitiveness and economic independence. On Apr. 9, the administration released an executive order announcing a 90-day pause on all reciprocal tariffs, except those imposed on China.

“For people who are expressing kind of a coherent view on why they are in support of tariffs, I think the idea is that if we put tariffs on imports, especially imported manufacturing goods, that foreign companies will have an incentive to build factories in the U.S. and would revive manufacturing employment in the US through this foreign investment,” Owen said.

Owen discussed the dramatic decline in manufacturing employment over the past 75 years, presenting a statistic that in 1950, more than 30% of American workers were employed in manufacturing, while today, it’s less than 8%. While globalization and trade, particularly after China joined the World Trade Organization, contributed to that drop, Owen stressed that automation has played a significant role. “Manufacturing firms are increasingly automated,” she said.

Critics of tariffs often argue that they function as a tax—one that disproportionately impacts low-income households. “Tariffs are a regressive tax,” Owen explained. “Low-income people spend a large share of their income on goods they buy, while rich people save more. So it’s going to be a particularly high tax rate for lower income households.” Even with the recent 90-day pause on tariffs, she said, the effective tariff rate is still very high.

In comparison with Trump’s broad tariff strategy aimed at renegotiating trade deals and addressing trade imbalances, former President Joe Biden left much of Trump’s first-term tariffs in place and raised some further. According to Barrons, the Biden administration left tariffs in place on $350 billion of Chinese goods that were imposed by Trump.

In January 2022, amid pressure from the American business community to lift tariffs due to rising inflation and ongoing supply chain disruptions, Biden responded to questions about if it was time to begin removing some of the tariffs by saying it was “uncertain” during a news conference.

“The main difference is that Biden’s policies were a lot more narrow,” Owen told The Spectator. “The current tariff policy of the Trump administration is to put tariffs on everything—all trading partners—regardless of trade surplus and deficit.”

“Tariffs are now just being implemented, so we don’t really have a lot of data about the effect,” she said during the presentation. “But this is where now we can think about what people expect to happen.”

To illustrate how expectations are already shaping the economy, Owen turned to several key indicators. “The first thing that has gotten a lot of headlines is what’s happening in equity markets,” she said, pointing to a graph of the S&P 500, a stock market index tracking the stock performance of 500 of the largest publicly traded companies in the U.S. “Equity markets are predicting negative consequences of these tariffs.”

Owen reminded the audience that, directly or indirectly, most Americans are affected by what happens in equity markets. “One reason that we should care is that equity markets are predictive. We think about equity markets as being a leading indicator for the economy,” she said. “They often predict downturns–not always–but they sometimes do.”

“Even if you don’t own any equities, over 60% of the American public does, and if you wake up one day and you’re 10% poorer than you were the day before, that’s going to affect your consumption, she said.” Right now, she said, the equity markets are “not very optimistic about the impact of tariffs.”

Owen then shifted to interest rates, another indicator of investor sentiment. “When we’re thinking about going into a recession, we should see interest rates decline. We don’t see that. We see the opposite,” Owen said.

“The US has often been considered a safe haven. When there’s lots of risk and volatility in the rest of the world, buy US Treasury bonds [because] that’s a really safe place to keep your money,” she said. Rising interest rates suggest that investors may be retreating from that view. “The fact that these interest rates actually went up is perhaps evidence that people are pulling back from the US economy,” she said.

“Both the bond market and the stock market are not giving an optimistic assessment of the tariff policy,” she said.

Owen then showed a graph that displayed a large spike in economic uncertainty, an index that is extracted from financial markets. She also showed a graph that tracks policy uncertainty through text analysis of newspaper reports. Both pointed to increased uncertainty and volatility.

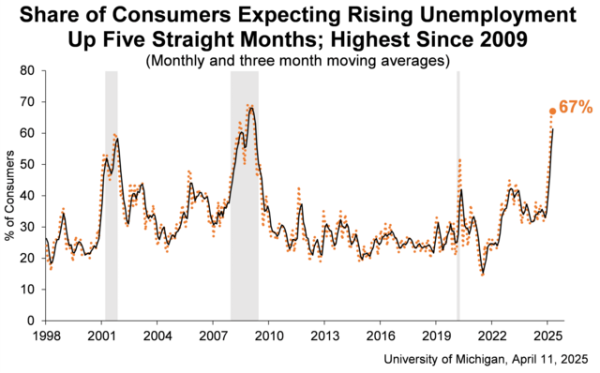

Owen presented a graph of consumer sentiment created by the University of Michigan based on a series of questions that the researchers at the university surveyed consumers with monthly. The graph showed that consumers are very pessimistic and expect high inflation and unemployment. “If consumers are acting on these beliefs, they are predicting a pretty big downturn and high inflation rates in the near term,” Owen said.

Although consumer sentiment is at a low, this has not always aligned with actual spending behavior in recent years. According to a January 2025 McKinsey & Company report titled “The ‘Value Now’ Consumer: Making Sense of US Consumer Sentiment and Spending”, even though US consumer optimism for the past couple of years has been lower than pre-pandemic levels and more than half of consumers reported mixed feelings or being pessimistic about the state of the economy, “consumer research shows that, even when we adjust spending for inflation, in aggregate, consumers are spending more than they were before the pandemic and are spending more each year.” McKinsey researchers found that despite expressing economic anxieties, Americans have been selectively spending more, driven by higher wages, low unemployment and a shift toward purchases that offer a perceived higher value.

The Empire State Manufacturing Survey revealed that in New York, “manufacturers are answering in a very pessimistic way,” Owen said during the presentation. “But one [question on the survey] that is particularly relevant is about whether or not tariffs are going to lead to more manufacturing investment.” The data showed a large decline in whether manufacturers are anticipating making more capital expenditures. “So this data that was released very recently is very pessimistic about how manufacturers are going to respond, and whether or not these tariffs are going to be an effective strategy to increase manufacturing employment,” Owen said.

However, Owen pointed out that the consumer price index (CPI), which measures the average change over time in prices paid by consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services, is still under control. “People are expecting higher inflation, but it hasn’t happened yet,” Owen said. “So that’s good news.”

Despite growing concerns around tariffs and equity markets, Owen acknowledged that “the labor market is currently in pretty good condition.” However, she said that may not last. “The employment condition is a lagging indicator, because firms tend not to fire people right away in response to a little blip… so often the labor market doesn’t respond until firms are really certain that economic conditions have deteriorated.”

Owen pointed to a chart tracking the evolution of the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for real GDP growth in the first quarter of 2025. The graph showed a steep decline in late February, with recent projections falling well below earlier expectations. While the Atlanta Fed’s estimate is at -2.2%, the New York Fed’s estimate, released last week, predicts a real GDP growth rate of 2.6%.

Owen expressed confidence in the American economy’s ability to recover from a possible recession due to strong institutions, rule of law and independent monetary policy, but she said we should ask ourselves whether or not we still have those conditions.

Owen ended her presentation saying that concerns about the investment climate place considerable doubt that tariffs will lead to the revival of manufacturing. “What are things that are happening that are not consistent with increased investment? Uncertainty—that’s usually associated with a decline in investment. Increasing interest rates makes investment go down. A relatively high probability of a recession in the short term. That’s not a good time to make an investment, right?”

She also questioned whether structural issues might be affecting the U.S. economy in the long term. “Concerns about institutional quality, concerns about long-run fundamentals that have kept the American economy growing strong for more than 100 years, are these things eroding?,” Owen asked.

From there, she opened the floor to questions. In response to a question about the administration’s pro-tariff arguments, Owen said “I think that there have been things that some of the advisors of Trump have said that make no sense. Like, how did they come up with the formula for the tariffs?”.

Owen referenced Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s assertion that tariffs will only inflict a one-time “price adjustment” on the economy. “When have you ever had a one-time price increase? That has never happened,” she said.

Another audience member asked whether Trump has the ability to fire Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who he has recently criticized. “Legally, no,” Owen said. “Powell’s term as chair is up in less than a year, and then Trump gets to appoint the new chair.”

She added that Powell has reportedly stated that he would use personal resources to fight against an attempt to remove him before the end of his term. “If I were advising Donald Trump, and he said, ‘I want to get rid of Powell,’ I would say, ‘Gee, why don’t you just wait? Because you have less than a year until you get to appoint your person and the fight that you’re going to get into given everything else you’re trying to do, it’s not worth it,’” Owen said.

When asked about the macroeconomic impacts of Trump’s immigration policies, Owen warned that shrinking the labor force could be inflationary. “And the Fed has kind of alluded to that,” she said. “[The Fed] has been super careful about what they say, because they don’t want to be perceived as coming out and taking a political stance.”

“I think it’s also possible if we’re deporting tax-paying immigrants, that’s going to have an impact on the deficit. We’re going to collect less in tax revenues,” she said.

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal titled “Trump is Everywhere Except in the Economic Data” says that the widespread concerns about tariffs, spending cuts, inflation and deportations leading to a recession have yet to show up in the numbers. “Imagine you didn’t follow the news or social media and watched the world only through economic data. You would not have guessed the White House changed hands in January,” wrote Chief Economics Commentator Greg Ip.

The extent to which Trump’s policies are expected to influence the economy depends on how much weight is placed on financial markets as predictors. “Some parts of the economy aren’t going to respond immediately,” Owen told The Spectator, “while financial markets are often forward-looking and respond immediately.” Even though financial markets, consumer sentiment and manufacturing are generally pessimistic, “we will only know for sure after it happens,” Owen said.