When one contemplates turning points for American society in the twentieth century, World War II is often top of mind. There is validity to this; World War II solidified the United States’ role as a global superpower, finally fully pulled the nation out of the Great Depression and cultivated an image of forward-looking American prosperity that John F. Kennedy and his family would develop further in the 1960s. However, I would argue that as we have moved through the last quarter of the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, the Vietnam War’s impact on our national culture has been much more prominent than World War II’s.

World War II portrayed a strong America that was united behind both domestic industrial projects and foreign military conquests. Presidents like Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush would attempt to harken back to this representation with the intention to entice citizens into that same postwar optimism, though they would be much less successful than the immediate postwar presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower.

The Vietnam War caused this image to come crashing down. The 1960s brought civil unrest among race relations and gender inequality, and as time went on it became increasingly clear that the war in Vietnam was not going to be the blazing success that the American people were promised. The purpose behind the war started off as an easily digestable fight against communism, but while things continued to get worse domestically congruently with young boys ceaselessly getting drafted and killed in Vietnam, that cause became much murkier.

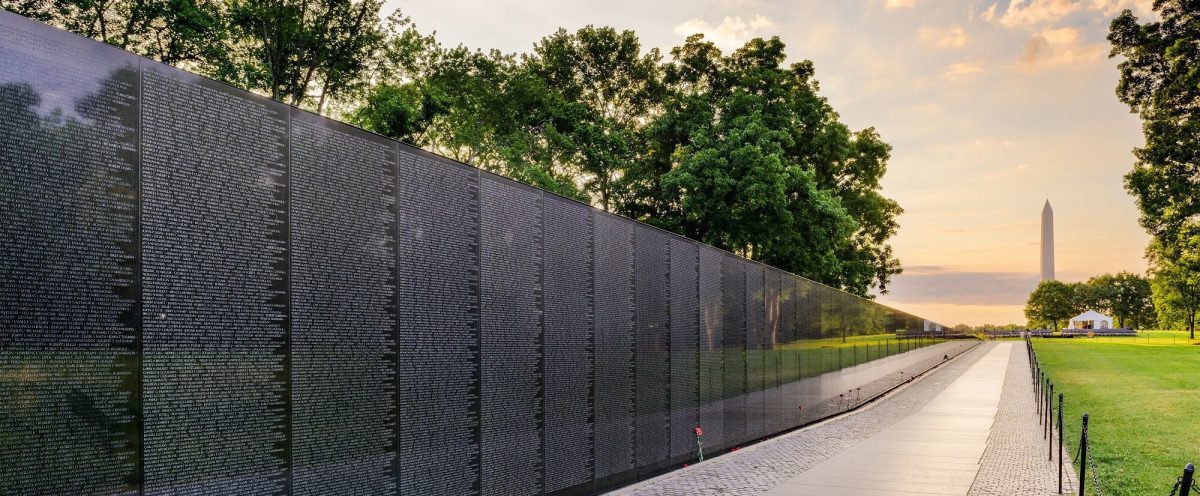

The war caused a deep distrust in government that was simply not present in the case of World War II, and this distrust has left a major scar on the American state of mind. If you drive around a quasi-rural area for long enough, nine times out of ten you will see a black POW/MIA flag to commemorate the trauma of the Vietnam war. All of the American soldiers who were kept as prisoners of war were allegedly released, but there has been so much secrecy and chaos surrounding the Vietnam War since its inception that there are many conspiracy theorists out there who believe that this may not be the case.

The internet and extremist news outlets like FOX and MSNBC have been able to prey on this distrust in American government and exploit it for continued attention and political gain. Issues are often rehashed and warped until they barely resemble the initial point in a manner that is not unlike the way in which the Vietnam War was initially framed to the general public. Yet, news outlets will present themselves as the only true source and claim that the viewer is actually reclaiming agency by choosing to get their news from that particular source.

Furthermore, what Americans crave more than ever in this day and age is relatability in their public figures, sometimes even more so than reliability. When many U.S. citizens look at career politicians, they are reacquainted with painful memories of newspaper images of Kent State University or monthly reports of deaths in their local communities, making the idea of an outsider entering the political sphere extremely desirous. These “outsiders” tell their proposed constituents that they’ve been right all along, their government has been lying to them, but once they enter office they primarily cut welfare programs or healthcare that their constituents rely on.

While World War II demanded more of Americans in terms of imagining a larger future, the Vietnam War’s direct impact is still very much felt in day-to-day life. The Vietnam War has placed pressure on presidents when presented with foreign conflict to have a 100% success rate in an attempt to erase the huge blemish the war has left in American memory. Additionally, the Vietnam War has left many Americans uncertain of what exactly the government’s role is in foreign conflicts, which has only been further complicated by the accessibility US citizens now have to millions of different, oftentimes ill-informed perspectives.