Rachel Cusk writes in her essay, Marble in Metamorphosis, which explores the symbolic and cultural significance of marble: “The artist and the dictator stand at opposite ends of the concept of agreement, which is essentially the concept of storytelling. As a story does, the created object seeks agreement: unless successive generations agree with the statement the object makes, it will be destroyed by time. The artist makes a bet on that future perspective, even at the cost of dispensing with agreement in the now. By contrast, the dictator tries to stop time and control the future, by staking everything on the present moment. Where the artist is often weaker than the things he creates, the dictator struggles to create something that will outlast him. Yet both are bent on commemorating their vision by embodying it in that which exists outside themselves, that which is concrete.”

The idea of legacy is embedded in every act that the artist and the dictator take. The artist creates pieces, often challenges social norms and entrusts future generations to comprehend and accept the work. Artists are the avant-garde; they challenge perceptions of reality and reinterpret common tropes. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp famously presented a urinal initialed “R. Mutt” to an artists’ society in New York City, provoking people to question their perception of what is considered art. Duchamp’s contentious piece brings to the forefront the conception of art as a societal agreement. Auction houses, dealers and the artist community coalesce to make a judging body that allows some people to succeed, while others fall through the cracks.

The artist pours their soul into a work in the hope that it can surpass their status. While a dictator, having already achieved an exalted status, struggles to preserve their name, whether through extensive warfare or through monumental constructions. Within the dichotomy of striving to become great and preserving greatness lies the distinction: artworks ripen over time, while dictators’ names often fall from grace. The act of preservation involves an intrinsic investment in the ego; there is a belief that one’s image is worth immortalizing. A dictatorship embodies a consciousness that they are superior—that God has ordained their appointment as leader. This consciousness permeates every creation. In the fear that the epoch in which the dictator’s acclaimed status may be forgotten, the dictator yearns to halt progress. There is a stale smell of stagnancy that hovers above the streets during dictatorships. While the artist, as vain as they might be, strives to create a work that far greater than themselves they are embodying an idea so close to the heart and mind that, if executed properly, will bring people to tears. The artist gambles that the current epoch will not persist, that change will come and that the artwork will coincide with the ideology that is being intimated in this new era.

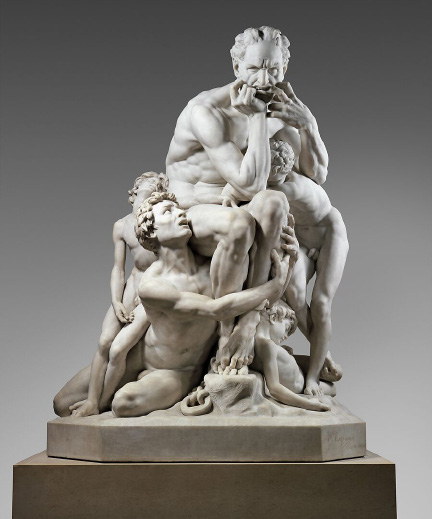

Cusk argues for the persistence of marble as a material, for its immutability in form, yet also its metamorphic qualities in representation and historicism. In stone lies the irony; while sculptors such as Rodin seem to have solidified their place in history, it is those monuments that we walk by each day that hold no memory, no power. Robert Musil said in his 1927 essay, “Monuments”, that “There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.” The dictator, conqueror and pillager try their best to be unforgotten; they place themselves in plazas and street corners, yet it is the pigeons who find their forms most appealing. One looks at a monument of a great dictator and their pomposity seems to repel us, yet we look at a sculpture that depicts raw emotion, and we are moved to put the figures on a pedestal. Looking at Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Ugolino and his Sons, one can feel the gnawing pain in the father’s eyes, as he is condemned to starve in a tower with his sons and contemplates cannibalizing them.

The artist and the dictator are striving for preservation; one attempts to preserve themselves, the other attempts to preserve an idea. It is the artist who succeeds. It is through Plato’s Theory of Forms that the artist is most closely understood. The artist strives for the Platonic form, for the imperfect expression of a perfect idea.