The professional tennis circuit is a grueling journey. Taking up ten to eleven months each year, the tour sees players travel around the world to play in different tournaments. The time change and surface changes alone (players compete on courts made of cement, clay, and grass at various times) pose significant challenges. No two tennis courts are the same, so players practice frequently before tournaments to get used to the unique speeds and height of bounce. Injuries, the overall cost of living and burnout throw several more wrenches into the mix.

The more matches players win, the more money they make. For the best players, this is a lucrative system. But for the lower-ranked players, performance in a tournament can be a matter of financial security. Andre Agassi, an American player who went on to have a Hall of Fame-worthy career, has documented his struggles to win enough money to get by as a teenage professional. He eventually got his breakthrough, but less talented players tend to be less fortunate.

By the end of the season, most players are running on fumes. The very elite (say, the top five on the men’s and women’s singles tours) generally accumulate sufficient prize money so that they can skip big tournaments if their bodies or minds cannot take the week-after-week strain. But the lower-ranked players, who do not have the luxury of millions of dollars to fund travel for their entire team and to pay a coach, a nutritionist and a physio, sometimes need to take part in a tournament in hopes of a big payday, mental and physical health be damned.

In May, Andrey Rublev (who was then ranked eighth in the world) said that due to having to pay his team during the pandemic while not being able to compete, he could not afford an apartment. At the time of the quote, he had earned $1.26 million in prize money in 2021. Even some of the elite players may struggle financially. Imagine the extra stress this puts on results — if a player loses early at a tournament in which they expected to do well, the financial ramifications can be severe, increasing the pressure further.

Most of the tennis calendar is played on hard courts made of cement, which is the material the courts at Hamilton are made of. Softer surfaces in clay and grass are also present, but due to costs, hard court is by far the most used surface on the professional tours. Since a big part of playing tennis well is moving around the court quickly to return shots hit into the corners, professional players are adept at sliding at the end of a sprint, allowing them to change direction quickly.

On cement, this is a grinding, shrieking motion that players go through dozens of times in every match they play. Even for a professional athlete, over the course of ten months with minimal rest and recovery, these slides add up to fatigue and sometimes injury.

The calendar can be so taxing that even the year-end finals, where the top eight men’s and women’s players compete, are skipped by players relatively often due to injury or fatigue. These finals are the fifth-biggest tournament of the year in terms of ranking points and offer huge prize pots, but at the end of the year, players have little left in the tank. In the 2019 women’s year-end finals, two players had to retire mid-match in the group stage, and a third was unable to finish a match in the semifinals. The stakes are not the problem. At some point rest is needed above all else. Except, for some, the money to continue playing tennis.

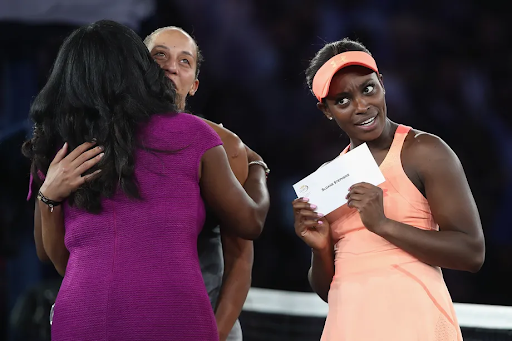

In this way, the end of the tennis calendar has become a broken system that is somehow necessary at the same time; a player competing while injured is dumb, yet it’s easy to see why they do it. These issues could be partially remedied by paying players a salary so that their finances did not depend solely on prize money and off-court endorsements. Or, by distributing prize money more evenly from first round to last of a tournament — at the 2021 Australian Open, winners took home $2.13 million while first-round losers made barely $70,000 (about 0.33% of the winner’s prize money).

Despite these obvious solutions, counting on this problem to be fixed is risky. Tennis has always been an elitist sport, from the enduring tradition of players being forced to wear all-white outfits at Wimbledon, (one of the year’s biggest four tournaments) to the lack of available highlights of matches that are longer than three or four minutes. Until this top-heaviness of tennis players’ finances changes, the sport will be stuck with a pile of injured players at the end of the year who force their broken bodies to compete anyway.