“Into the Hamilton Archives” is a recurring column that seeks to explore the often forgotten texts and artifacts in the Hamilton College Archives. In the last issue, I discussed a statement from 1863 by Hamilton College President Samuel W. Fisher. In that statement, President Fisher detailed the disorderly conduct of the junior class who caused disruptions in response to their German class not being shortened like they had hoped. Feeling disrespected by the faculty, a significant amount of juniors left the College. I linked these rebellious actions to the rousing attitudes of the Civil War and the uneven power dynamic between faculty and students at the time. I want to quickly amend the last sentence of the previous issue where I stated I would analyze the students’ response. After doing more research, the response letter I discuss below was written by three trustees who were Hamilton alumni (one of whom shared the same first and last name as a current student at the time) hence my initial confusion. As such, in this week’s issue, I will analyze the trustees’ response to the President’s statement. While a student response would have been more exciting to read about, there remains some value in understanding the stances of the administration.

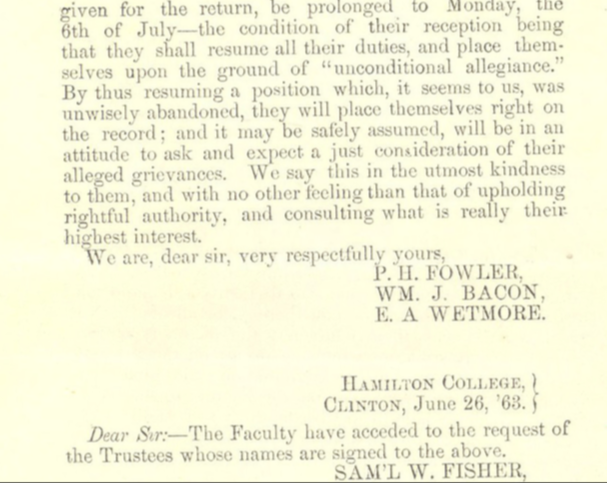

After reading the President’s statement, the three trustees — P.H Fowler, WM. J. Bacon and E. A. Wetmore — met with the juniors deemed as the main perpetrators of the disruptions. Siding with the faculty, the three men agreed that the juniors were in the wrong. They wrote as follows:

“The class were entirely wrong in the mode which they took to obtain redress of their alleged grievances. In reference to those grievances, it is unnecessary to say anything. If admitted to be such as stated, and of such character as to justify a demand for redress, our opinion would not, thereby, be affected. No matter what was their character, the members of the class were unjustifiable in refusing to attend their usual exercises, and in forming a combination, the object of which must have been to compel the Faculty to accede to their demands; and, (nonwithstanding the right step which they took in ‘annulling all combinations and returning to their allegiance,’) they were especially wrong in deciding to leave College on Monday morning, (the 23rd,) without waiting for the result of the meeting of the Faculty with a Committee of the Class, which had been promised for Wednesday morning.”

Fowler, Bacon and Wetmore saw the junior class’s conduct as unnecessary and disrespectful to the Faculty. Though they acknowledged the juniors’ attempt to return to their classes and follow the rules, Fowler, Bacon and Wetmore ultimately decided that the juniors committed unjustifiable wrongs. The three men continued to support the faculty, stating that the faculty acted “‘with all the leniency which a proper respect for themselves, and regard for the good order of the Institution would authorize;’ that their proceedings have been right and just and that their authority should be sustained without impairment, or possible question.” Fowler, Bacon and Wetmore saw the faculty as having good moral character and maintained that the College should allow the faculty members involved in the conflict to stay at the institution.

The three men end their response with good faith toward the junior class, hoping that they return to their responsibilities. They expect the juniors with good character to honor their duty to their friends and uphold the cause of education and order. Maintaining their authority as members of the board, the trustees unilaterally supported the actions of the faculty and president. While they acknowledged the possible good character of the rebellious juniors, they ultimately valued order.

Though the nation was undergoing a civil war during this time, the trustees felt that it was necessary to maintain some semblance of peace and normalcy on campus. While it is unsurprising that the trustees would side with the faculty and administrators, it is still valuable to see what the correspondences were like between the President and the Board. A sense of deference and mutual respect is seen in both the letters, though President Fisher assumes some suburdonination since he asked for advice. This correspondence brings up questions about the power dynamic between the President and the Board today. How much power do the Head of the Board or the College President really have both historically and today? Did this power dynamic change as leadership changed?

Reading both letters in tandem allowed me to better understand the relationship between President Fisher and the trustees, especially in regard to a crisis. Next week, I will pivot to something a little more lighthearted: Annie the Musical. The playwright for Annie was a Hamilton alum, and his original mansucript will arrive in the archives very soon! I will try to cover both his legacy and the actual manuscript in the next two or so articles so, stay tuned.