When I hear the words “no one is safe” come out of a prominent politician’s mouth on national television, I cannot help but freak out. My mind starts racing: Is this the start of the COVID-23? Are we on the brink of nuclear armageddon? Has climate change reached a point of no return?

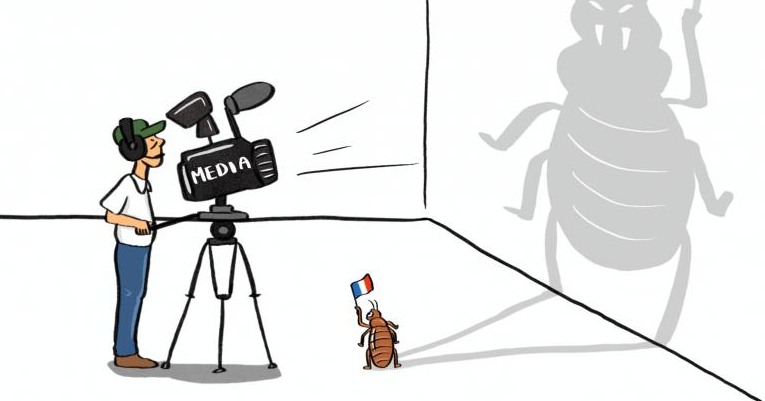

Although I am no betting man, among the hundreds of worse-case scenarios I have theorized, never would I have imagined bedbugs being the source of human downfall. Yes, you read that right: microscopic, wingless insects throwing a developed European state into complete chaos. In early October 2023, France’s unfortunate fate crossed paths with this bloodsucking pest, wreaking havoc on all levels of society. From high-ranking political elite to common citizens, sightings of bedbugs in metros, movie theaters, cafes and airports have left many frazzled. You might think France is an isolated case, but remember this silver lining: while Paris might have bedbugs, so do New York City, Tokyo, and London. In other words bedbugs are everywhere, and their attachment to humans does not fall short of the European mainland. How long have bedbugs and humans coexisted together, and what solutions are available to get rid of these bloodsucking insects? More importantly, how do we ensure a bedbug-free future for humanity as a whole? Understanding the potential answers and limitations to fighting bedbugs is critical in ensuring human wellbeing in France and beyond.

Written recordings of bedbug infestations date back to ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire, proving to have been household pests for over 3,500 years. Long before the creation of pesticides, the Romans and Greek used bedbugs for various medicinal purposes, while the Egyptians drank bedbug juice as a remedy for snake bites. Centuries later, in the early 1800s, bedbugs in London hostels became such a nuisance that individuals recommended getting drunk in hopes of a good night’s rest. Early 19th century neo-industrialized London became prime breeding ground for swaths of bedbugs due to the close proximity of its residents and more frequent physical contact across the city. In the most drastic of cases, city officials did not hesitate to burn down buildings in order to squash potential insect insurgencies. A century and a half later, the rise of DDT during World War II, initially intended to protect troops from mosquito-borne illnesses, quickly spread to killing bedbugs in cities across the globe. Alongside the highly toxic pesticide, Americans further popularized washing machines and vacuums, virtually eliminating the bedbug population within developed nations. However, once DDT was classified as a cancer-causing agent and banned in the U.S., bedbugs were given a lifeline back into human existence. Ever since 1972, bedbugs have repeatedly been sighted across the globe, including spikes in Australia, the UK, Japan and recently France. While it is clear humans and bedbugs have a long-lasting shared history, what explains recent rises in these bloodsuckers worldwide?

Among the many reasons for this resurgence, human innovation and globalization has only worsened the situation. Bedgbugs crave warm bodies in densely packed environments, notably taking advantage of rapid urban development within cities to build nests and repopulate. In recent times, increased international travel has provided the ideal vehicle for bedbugs to cross continents in a matter of hours by hitchhiking in suitcases and luggage. Over the past decades, summer travel has been correlated with a rise in bedbug sightings as per the New York Health Department. In France’s case, expert entomologists believe the country’s highly attended Paris Fashion Week show, held in late September, was a key catalyst for bedbug spikes.

Although man-made causes are to blame, bedbugs have also evolved pesticide-resistant antibodies, nullifying the majority of insecticides historically used to kill them. As per the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, most classes of insecticides, including DDT and pyrethroids, a potent chemical agent in household pesticides, are no longer useful against bedbugs. Alternative pesticides, including dusting powders and sprays, have proven ineffective.

Nonetheless, the prime solution to getting rid of bedbug infestations still remains fumigation, a highly toxic procedure many Parisian residents have turned to during these desperate times. By suffocating insects using a mixture of gaseous compounds heated at temperatures exceeding 113 degrees Fahrenheit, fumigation undoubtedly produces the most fruitful results.

Despite its high success rate, fumigation services are costly, which oftentimes excludes low-income communities from acquiring these necessary services. If France wishes to suppress this bedbug insurgency, fumigation subsidies for underserved communities within Paris and the nation as a whole must be implemented. Until world leaders come up with a cost-effective solution affordable to all, bedbugs in France and abroad are here to stay.