Rafael Nadal has a complicated relationship with the Australian Open. He won it in 2009. Ranked #1 at that point, he advanced to the semifinals easily. Once there, he played Fernando Verdasco in a legendary match. Verdasco hit every ball as hard as he could at the edges of the court in an effort to make Nadal run as hard and as much as possible. It was the most high-risk strategy imaginable, but Verdasco was shockingly accurate in his endeavors. Nadal answered the call, chasing down Verdasco’s bullet shots for a staggering five hours and 14 minutes. The intensity of the match was so extreme that when Nadal was a point away from winning, he started to cry. “I wasn’t crying because I sensed defeat, or even victory,” Nadal wrote in his autobiography,

Rafa

, “but as a response to the sheer excruciating tension of it all.”

Nadal won that match, then managed to regroup physically for a final against Roger Federer, who he beat in another long, draining match. Nadal had not really played his best in either match, rather, he had to overcome his opponents’ great play with all the resolve and consistency he could muster. It was a spectacular victory, a reward for all the little parts of his game he had improved in the past years. Juan José Vallejo, a former tennis writer whose opinions I take as gospel, called this the most impressive feat he had ever seen on a tennis court.

In the years after 2009, the Australian Open has been a place of pain for Nadal. Injury either hampered him or forced him to withdraw altogether in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014 and 2018. He made the final but lost narrowly in 2012 and 2017. To make matters worse, he had come from behind in each final only to blow a lead at decisive moments. He made the final yet again in 2019, but Novak Djokovic annihilated him.

Nadal and the Australian Open have had the sport-version of a will-they-won’t-they. He has played well there many times, but since 2009, has always been blocked by an opponent’s great play, his own lapses, or pure bad luck. He may have played better on average at the Australian Open than the U.S. Open (which he has won four times).

Over time, Nadal’s chances at the Australian Open have decreased. He is 35 now and can no longer run endlessly as he did in 2009. He has overcome about a million and a half injuries, including a congenital disorder in his tarsal scaphoid (a bone in his foot). This injury is not treatable, and Nadal has had to negotiate it gently over the years to be able to play — erasing the pain is impossible, but he can keep it to a manageable level.

Last year, the injury flared up badly. Nadal played only two matches between the French Open in June and the end of the season. Five months ago, he was on crutches. Shortly before the Australian Open, he caught COVID and had a few days of severe symptoms. He recovered in time to fly to Australia, but he was short on recent match practice, even after a warm-up tournament. Going into the Australian Open, his odds seemed worse than they had been in many years.

Nadal, somehow, made the final. He played well, but strong performances from his opponents did not really materialize — Nadal still looked physically fragile, visibly tiring before the end of matches, but was able to win without significant scares.

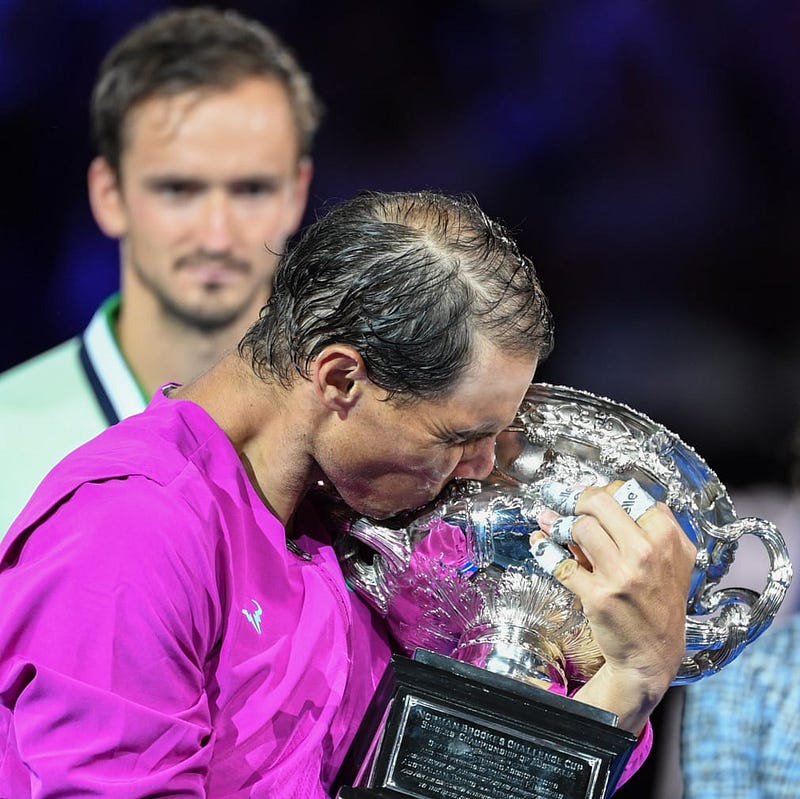

Then came the final. Nadal played Daniil Medvedev, who was ranked second to Nadal’s sixth, is ten years younger, and had outperformed Nadal as of late. He had developed a fierce affinity for extending points with amazing defense — dangerous for Nadal, who many were thinking needed to play an economical match to have a chance at winning.

Medvedev won the first set of the best-of-five match easily. Despite Nadal having a bunch of chances to win the second, Medvedev won that too. At one point, Nadal trailed 2–6, 6–7, 2–3, love-40. If these numbers mean nothing to you, it is basically the equivalent of a football team trailing 30–0 in the middle of the fourth quarter. It is not a mathematical impossibility that you can win from there, but it will not happen.

Except for Nadal, it did. It was unsurprising that he refused to fold in the third set; his trademark is fighting until the last point. But it was shocking that he pushed Medvedev into tiring faster in the fourth, then survived a near-horrific choke in the fifth. The match went longer than anyone could reasonably expect, longer than I thought Nadal could play. It was five hours and 24 minutes by the end, the second-longest match he has played in his eighteen-plus year career. Nadal smiled in disbelief as Medvedev was unable to reach his last shot. A second Australian Open title had seemed out of reach for years, this year more than ever, yet it had found its way into his arms. He looked so joyous in the moment that the fact he had won a 21st major title, more than any man in history, felt almost irrelevant.

Nadal has spent his career overcoming obstacles, whether they be his opponents or one of dozens of injuries. This last achievement was one of his most unexpected, and with it coming so late in his career, it will taste all the sweeter.