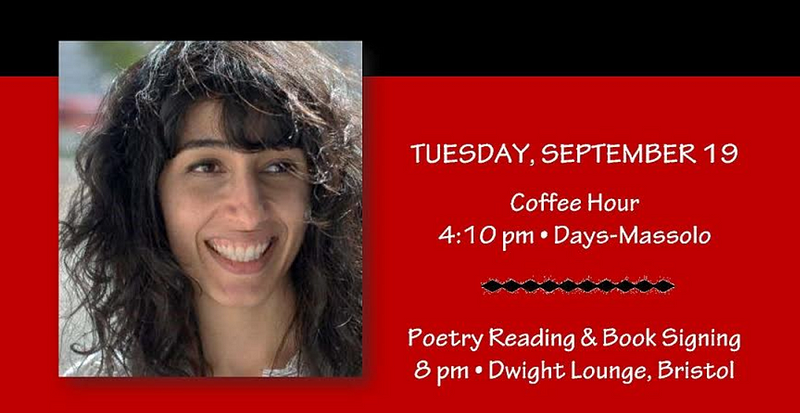

“I believe in poetry that makes visible the invisible and audible the inaudible,” said award-winning poet Solmaz Sharif during a reading in the Dwight Lounge on Sept. 19. In a mixture of personal reflections on her own life and profound commentary on today’s society as a whole, Sharif expressed the beauty of poetry as a way to understand one’s self and one’s surroundings.

Sharif was born in Istanbul, Turkey and holds degrees from University of California Berkeley, where she studied and taught alongside June Jordan’s Poetry for the People activism program, and New York University. As a National Endowment for the Arts fellow and Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award winner, her works have been featured in

The New Republic, Poetry, The Kenyon Review, jubilat, Gulf Coast, Boston Review, Witness,

and more. She currently teaches at Stanford University as a Jones Lecturer.

Additionally, her debut poetry collection,

Look

, was a finalist for the 2016 National Book Award.

Look

focuses on the consequences of warfare especially as it relates to America’s invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, using the fragmented narratives Sharif had heard from her Iranian parents. The collection also uses words from the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms as a way to show how language affects our desire to act in violence. During the poetry reading, she read multiple works from her collection, including “Drone”, “Personal Effects” and “Mess Hall.”

During the reading, Sharif expressed her conflict with the use of authenticity when writing. The topic arose specifically during a discussion over coffee with members of the Hamilton community earlier that day. Shementions,“Alotof the conversation started to circle around who gets to write about what, what one’s kind of relationship to the material is, and how that then decides whether or not you have some kind of ownership over that material.”

Even so, Sharif admits that

Look

, alongside many of her other works, attempts to make sense of what she does not know. “I’m trying to explore [authenticity] a lot in this book because of my own relationship to war and my own relationship to the family that I write about is one that is distant.” She comments, “I was raised apart from them; I was raised outside of the war that was happening and so my own understanding of it was happening from the own stories that I was hearing from family or through news media we hear.”

During her piece, “Personal Effects,” for example, Sharif recited, “According to most definitions, I have never been at war. According to mine, most of my life spent there.” For Sharif, though she herself had not experienced such war-filled lifestyles, her pieces above are ways understanding the history she has been told as a child and “fill[ing] the silence in [her] own family.” She then hopes that her pieces can be used not only by herself to better understand her family, but by others to hear a narrative that is not usually audible to the world.

Sharif’s deep passion to understand her family’s past and the history of her people is an admirable desire representative of the idea that we not only write to understand, but we listen to understand. While her pieces provide a sense of comprehension toward her own cultural identity, readers can realize the reality of lives other than their own.

“We write toward what we don’t know, ultimately,” Sharif expressed. “You’re trying to find something and trying to name the something, and writing is born out of that desire.”