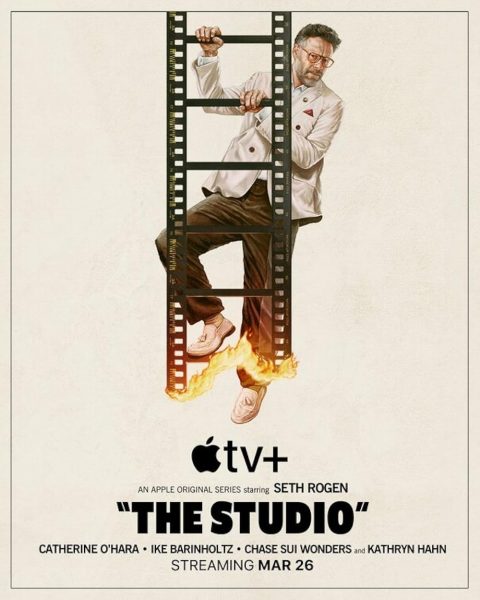

“Oh, God, it’s so humiliating,” Patty Leigh (Catherine O’Hara) cries at the door of her Architectural Digest mansion in front of her studio-head successor Matt Remick (Seth Rogen). She sports a million-dollar frown while Remick covers his $10-million dollar one after paying that amount for a Kool-Aid-licensed Martin Scorsese screenplay on the Jonestown Massacre. The Studio is not your modest, outsider-looking-in take on Hollywood that HBO’s Entourage provided for several years. Instead, we follow Remick, an established insider who cosplays as an outsider from within. But all we really get from The Studio is a cast full of A-list actors waxing poetic about their own industry. Not to mention, with the help of a presumably large Apple TV+ budget that makes this seemingly altruistic satire on the industry that they are entrenched within feel as empty as the calories in a glass of the aforementioned sugary drink.

Remick has just taken Leigh’s job after promising to Continental Studios boss Griffin Mill (Bryan Cranston), the human embodiment of corporate greed, that he would retire his auteur-obsessed ways in exchange for prioritizing the bottom-line. Remick’s first test to sell himself out is to find a director for a Kool-Aid-licensed film as a rebuttal to Sony’s success with Barbie. Mill sees the success of Barbie as a product of its brand-power, but Remick believes that writer-director Greta Gerwig was the creative light behind the effort. Film studios have always withstood internal disputes between upholding values of boundless creativity versus the reality of what works at the box-office, but Remick does not think the two goals are mutually exclusive. But he is the wrong—and this is more importantly, too late of a time—person for this sort of analysis.

The series is produced and bankrolled by Apple, but ironically ignores the true demise of independent filmmaking in exchange for its focus on major studios as the simultaneous gatekeepers and executioners of auteur filmmaking, as Remick pontificates upon with a total lack of self-awareness. While studios remain the most well-funded and easiest routes to box-office prosperity, streamers are the actual threats to contemporary examples of what cinema Remick desires, like that of the efforts from NEON or A24. Former outsiders to the film production industry, like Amazon, Netflix and of course, Apple, have dipped their toes into it, eschewing the normal outsourcing of box-office premieres and third-party marketing schemes for a fully insulated approach to the business.

The Studio insists that a film like Barbie is the apex intermingling of prosperity between the business and creativity of filmmaking, but this is a conceited perspective. Remick himself acknowledges that Barbie is a major-studio product of Sony, while he works for “Continental Studios,” an overt parallel to a studio like Sony. But he somehow misses that the problem is not the disintegration of auteurist filmmaking as a whole, but of Hollywood’s consumption of it in exchange for redundant intellectual property and an adverse attitude toward novel world-building. This is exemplified in the first episode, where Remick has to turn Kool-Aid’s IP into a box-office smash, despite his desire to uphold the artistic integrity that has defined his reputation prior to his promotion. In the process of trying to play both sides, he buys and kills a Scorsese script that could have solved both his business and moral dilemmas, but his eagerness to please—whether it is Scorsese or Mill—leads him to a final decision on the matter that upsets everyone, including himself, and is so foolhardy that even layman viewers can recognize his short-sighted business acumen.

Remick’s character oscillates between moral squishiness and intellectual self-righteousness, where he finds himself choosing between extremes at all times, effectively portraying Hollywood as a zero-sum game. One that requires its champions to either sell out or make obscure arthouse work that simplifies the film industry into a homogenous binary blob with no space for increasingly prevalent and prominent sub-sectors of streaming and independent work. One character even obliviously acknowledges this unjust simplification; The Super Mario Bros. Movie (2023) raked in dollars but received little acclaim. This mutually exclusive perspective is not reality, as demonstrated by the successes in both worlds by films like NEON’s Anora (2024) and A24’s Everything Everywhere All at Once (2023).

More than how conceptually misguided the series feels at times, its dialogue and pacing have a fake urgency that display a surface-level understanding of what makes the speed of an Adam McKay or Aaron Sorkin effort work. There is a Succession-level crudeness to the dialogue without the expositional value that these verbal idiosyncrasies provided for the HBO show’s characters. Additionally, the series is shot in a one-shot style of constant motion–where scenes are long and active and only eventually abruptly interrupted by a cut. An ongoing percussion sonically supports this rapidity, suggesting an accompanying crescendo of narrative peaks and pits that are so tentative that it makes these aesthetic decisions feel more stylistic than substantive.

Rogen plays Remick with his quirky expressiveness that makes his fake persona feel pointless but not as grating as his surrounding cast. His right-hand man Sal (Ike Barinholtz) has the facially expressive humor of a bad Saturday Night Live sketch, where loud and goofy is supposed to equal funny, while marketer Maya Mason (Kathryn Hahn) dons high-fashion and a Stanley mug as an abrasive valley-girl caricature that is as out of touch with contemporary culture and trends as she claims Remick to be.

Entourage had longevity and success because it felt like you were living vicariously through the rise and fall of its main characters, all of whom had their own respective storylines with enough breathing room to get invested in each. Instead, Remick is so central to this supposedly ensemble effort that it feels like we are getting a critical look at Hollywood merely through Rogen’s lens and it is not as interesting when the criticism comes from inside the house.