The day after the Martin Luther King Day commemoration on campus, our email boxes were assailed with news of the latest episode of the Common Ground saga scheduled for March. On this occasion, the event will star Reince Priebus (Republican) and Jim Messina (Democrat).

The whole notion of Common Ground is becoming more and more perplexing, given the state of the nation and the more major urgencies on the list of national items than staging mild “civil” contestations between former political officials of the Republicans and Democrats, especially when at least three of the episodes thus far have been so identical in the choice of presenter and theme as to render this fourth episode even more meaningless. What is the essential difference between the Rove and Axelrod tango, the Dubke and Elias parry, and this new Priebus and Messina tussle? Less salad dressing?

In the particular case of Reince Priebus, the question is: Will he be truthful in an environment where truth is still, supposedly, held in high regard? Will he, as a former chief of staff, offer a critique of the President’s documented lies on every conceivable issue? Will he find a modicum of contrition for his role in promulgating and buttressing, and then working for the most openly racist and sexist president in modern U.S. history? Very unlikely. For his part, Messina will invoke the “we are the nice guys” mantra. The outcome of the whole episode will only be a tick in the box for the college: “we successfully staged another Common Ground.” This is what Sara Ahmed, in her book

On Being Included

, calls the “manufacture of cohesion.”

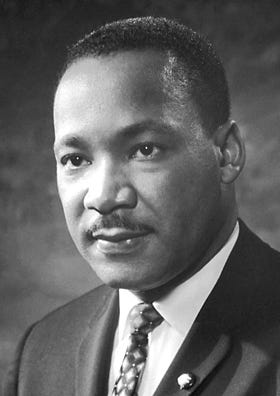

As the announcement of the upcoming event fell near MLK day, it might be useful to draw parallels between King’s experience and the current situation in the U.S. in the light of Common Ground.

For starters, if we transpose time and context, King would not have fit the bill for an invitation to a Common Ground event. In the period before his assassination, King was being assailed from all sides for going too far in expanding his civil rights activism. As he railed against the “giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism” elements in the NAACP cautioned him; the white church, for the most part, detested most of his actions (see King’s “Letter from a Montgomery Jail”); and civil rights moderates tried to temper him: “We are already succeeding, Martin; why talk about the Vietnam War and labour conditions?” This was the mantra back then. Meanwhile, the FBI carried on its merry work of surveillance and repression of King. By 1968, his disapproval rating hovered at over 70%.

In essence, it is the folks who were warning King against getting into labor disputes and his anti-Vietnam war stand who would be invited to a Hamilton Common Ground event today. The gradualist approach of King’s rivals and colleagues would be invoked as “civil discourse.”

It is now common knowledge that King was ahead of his time. Even the references to King’s “dream” are out of context, along with the dreamy, impractical endeavors of various savants that continue to allow travesties of justice to run amok. By 1968, King’s dream had faded substantially. He was increasingly isolated. After his assassination and for the 50 years since the safe labelling of his legacy continues to hone in on the “dream” rather than of the man’s courage in standing outside of, and against, the suffocating embrace of the mainstream. And colleges, including Hamilton, love that safe “middle” ground.

But back to the “Common Ground” of the moment. This criticism is not a call for uncivil discourse, but a demand for civil discourse that is grounded in openness and honesty on the many problems we face, and that propels us to action, not lulls us with banal and comforting pleasantries.

The money utilized for this ongoing charade could be better spent elsewhere. What we need now is a “common wind” of change, a force that is activated not by a desire to please all “sides” on issues where truth stares us in the face, but one that propels us into taking positive action in defense of truth and justice.

I also noticed that in the latest advertisement, as against past headline notifications, “Common Ground” is placed in quotation marks. Is this a tacit concession or a subliminal recognition that the concept of common ground is a delusion? Perhaps there will be a further shift in the fifth round of speakers, to the more accurate “uncommon ground” with all its implicit and challenging ambiguities.

Yours Sincerely,

Nigel Westmaas