By Ghada Emish ’19, Contributing Writer

When I tell my classmates that Cinema Studies is one of my concentrations, I usually receive a surprised facial expression that the Cinema Studies program even exists at Hamilton. Well, it is a concentration, and it has changed my life! Cinema and Media Studies is the name of the department, but students have the option to specialize in either cinema, media, or both. I have consciously chosen to focus on cinema.

The department has allowed me to grow through the opportunity to independently design my course of study. I mostly recognize the value of this education in my exploration of classical Egyptian cinema through research. However, classical Egyptian cinema is not a topic that one easily stumbles upon. There are few sources that focus on cinematography, and the artistic worth of the industry.

I suspected that I would specialize in film after taking “Intro to Russian Film” in the spring semester of my first year. For the first time, I was exposed to academic material that elaborated on the complexity of film for the socio-political implications embedded in its visual narrative. At this point, I realized that the language of film is powerful and wanted to learn more about it. So, I registered for “Intro. to History and Theory of Film” the following semester, with the only professor at Hamilton who specializes in film: Professor Scott MacDonald.

The introductory course is designed to expand our understanding of “what film can do,” in MacDonald’s words. I confess, I was frustrated with watching experimental films in the course. I was so accustomed to watching narrative films that I did not understand how to appreciate experimental films, but the class ended up teaching me how to do just that. The class is composed of two three-hour sessions per week, in which discussion follows film projections. The only assignment is to contemplate the films through writing.

It was an encouragement to take my time seeing these films and reflect on them. I realized that watching film is a process. It takes time to adapt one’s eyes to seeing what a film does. This class introduced me to reading a film. In my mind, the class inspired appreciation and respect for the medium.

In February 2017, I declared a cinema — and media — studies concentration. While I have been fascinated with classical Egyptian cinema since childhood, as a student of cinema, I still knew nothing about the world in which these films were produced. I continued to watch classical Egyptian cinema at my leisure. With the knowledge I acquired from film classes, I read the films differently. I wanted to learn how these films were made, and what distinguished their visual authors. So, for the past two summers, I conducted research on the industry. What I learned in class about reading film was instrumental in my research journeys.

To take a variety of film classes and improve my French language skills, I spent my junior year in France. The Hamilton in France program offered me opportunities much greater than I imagined. Living in Paris, I took cinema classes at two French universities and did an academic internship at the European Independent Film Festival. I even — deliberately — chose to take a class on experimental cinema. It was a huge lecture class that exposed me to the artistic and intellectual roots of experimental film. I was one of a few foreign students in this course at a reputable, public French university. I appreciate the course not only for its academic gain, but for the experience I had being in that classroom.

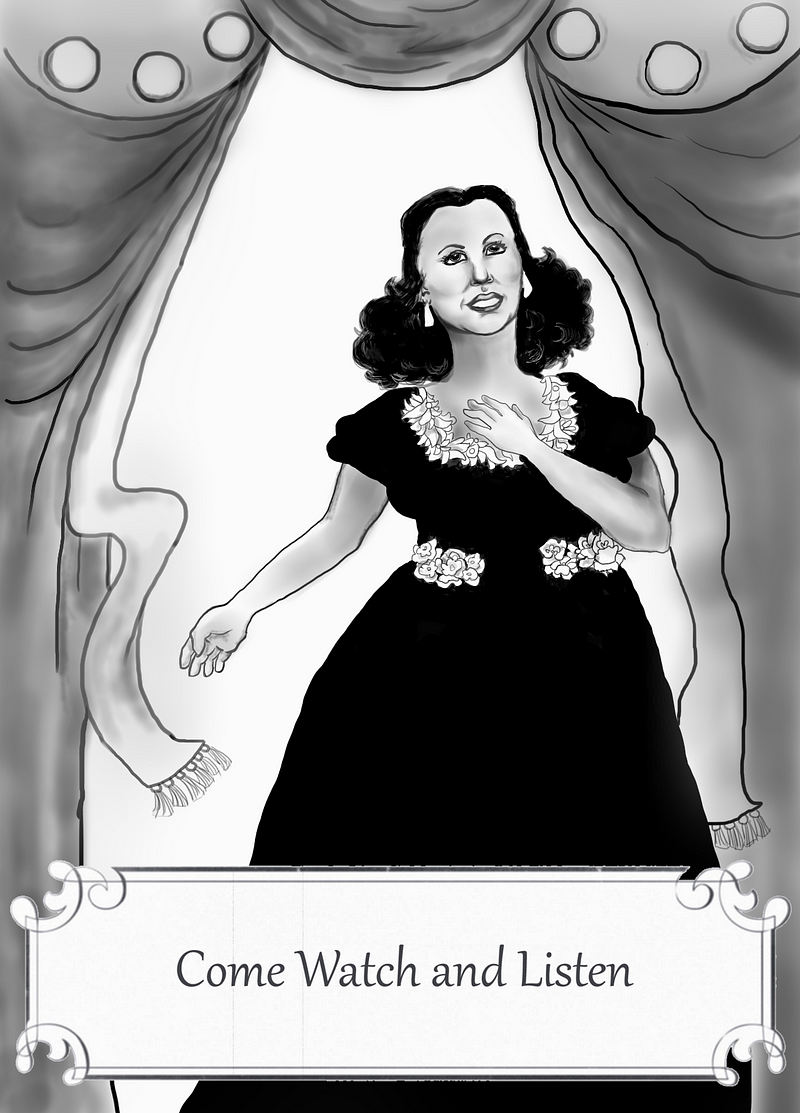

This semester, The Spectator has generously allowed me to publish a writing series on selected topics in classical Egyptian cinema. The articles in the series will be accompanied by a visual supplement that interprets the written analysis. Pippa Schwarzkopf ’16 has agreed to collaborate on the series by doing the illustrations. I first worked with Schwarzkopf on a similar project that was an assignment in the class “Visual Narratives: Images within Books.”

The Onset of Classical Egyptian Cinema Through Musical Film

Research on this topic took place through an Emerson grant in the summer of 2017, with Professor Scott MacDonald as my advisor.

It was in the late 19th century that Egyptian people took to listening to talented singers who would perform in the comfort of their customers’ homes, in the public cafes, or at the theatre. The rise of the musical film genre offered an additional way for Egyptians to enjoy listening to talented singers, but with a visual supplement. The musical film is the first genre in Egyptian cinema and the first type of cinema to achieve immense popularity in Egypt. One of the first Egyptian musical films is White Rose (1932), which featured Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, acclaimed musical composer and singer at the time. White Rose was the first Egyptian film to be externally distributed; it was mainly celebrated for the performances of the talented Abdel-Wahab.

The late 19th century in Egypt also witnessed a modernization wave led by the Khedive Ismail, the Egyptian ruler appointed by the Ottoman State. Cinema historian, Mahmoud Ali, mentions in his book,

The Dawn of Egyptian Cinema

that the first film projection in Egypt, on November 5th, 1896 in Alexandria, happened three months before Egypt’s first tramway was installed in Cairo. The most popular Egyptian musical films were influenced by theatre, which were particularly popular in the 1920s.

Theatre flourished after the arrival of director George Al-Abyad from Lebanon, who established a successful theatre troupe, where several film actors started their careers. One of these actors is Youssef Wahbi, who directed musical and non-musical films with a heavy theatrical influence. In making his film,

Love and Revenge

(1944), he shot the musical scenes in a style that corresponded to more a musical performance given on a theatre stage than it did to a film sequence. An example is the musical performance, “Merry Nights in Vienna,” which, besides being shot in an actual theatre, opens with the onset of a dance performance taking place on stage.

In capturing the musical sequence, the camera does not move; rather, it catches shots of the main singer, the dancing partners surrounding her and the view of the stage from an audience perspective. With the lack of any plot development throughout this musical performance, it becomes completely irrelevant to the film. It is as if the viewers only paid for a film ticket, but, in fact, had the chance to see both a musical performance “at the theatre” and a film!

Togo Mizrahi is the one directors who, mostly, integrated musical sequences as an essential part of the plot development. Mizrahi did not work long enough to develop his style; his career only included four musical films between 1939 and 1944, with singer Laila Mourad as the lead actress.

Despite the promise of Mizrahi’s films, they did not achieve as much popularity as the those by director and producer Anwar Wagdy. Active in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Wagdy was determined on making films, also starring Mourad, with glamorous musical sequences, but they were not always relevant to the plot. Wagdy’s films were critically praised for non-musical sequences with complex montage. But it was the editing skills of, later-to-be acclaimed director, Kamal Al-Sheikh, that were behind the composition of these sequences. With the prioritization of including musical sequences over the cohesion of plot development, the musical film genre never reached its full cinematographic potential.

During the age of the musical film genre, very few directors created non-musical films, which appealed more to film critics than to the public. An example is the neo-realist film Determination (1939) by Kamal Selim, which demonstrated a promising talent in using the camera to reflect on the characters. However, Selim did not live long enough to develop his style.

The early 1950s witnessed the appearance of directors who wanted to escape the light quality of the musical film formula. Examples are Al-Sheikh, Henry Barakat, and Youssef Chahine. Slowly, such directors produced films in other genres, with a lessening inclusion of musical sequences, and were critically praised for this endeavor.

While the musical film genre is a cultural asset for its musical performances, it provided a practice tool for some directors to hone their skills and develop their own stylistic trademarks. Later, these directors had full authorship of their films and the market slowly became more flexible to accommodate non-musical genres that included no music except in the soundtrack. These directors’ more promising films reflected on significant political themes, were selected at international film festivals and received significant critical acclaim.