This year marks the tenth anniversary of the College’s need-blind policy for first-year domestic applicants. This policy ensures that when potential students’ applications are reviewed by admissions, their family income does not play a decisive role; in other words, the admissions committee cannot deny a student admission to the College based on their family income. In theory, this policy is important because it allows students’ personal achievements to speak for themselves and evaluates all students by common standards, especially for those who are affected by factors outside of their control.

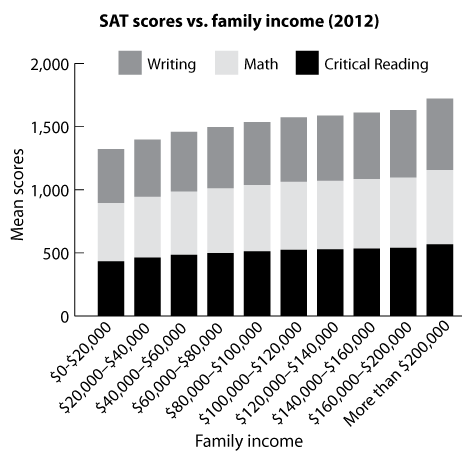

As much as I would like to believe that the College’s need-blind policy fulfills these goals, I know this is not completely true. The College still requires standardized testing scores, which functions as a de facto measure of family income. These tests, commonly known as the ACT and SAT, are rigged for students of higher income to perform better. The tests were known to be skewed towards success for students from high-income families even before the “Operation Varsity Blues” scandal, which exposed celebrities for having bribed test facilitators to doctor high scores on the SAT so their child would be admitted to college. Further, high-income families have access to private tutoring services and possess the means to pay for students to take standardized tests numerous times. Studies have repeatedly shown that higher income students have better chances at raising their scores with successive tries.

Not only are the tests unfair to lower income students, but they also disadvantage students with learning disabilities. Though students with a documented learning disability can be given extra test-taking time, this doesn’t always help. Some students — regardless of intelligence — just not good test takers, which limits the schools they can apply to because standardized tests do not demonstrate whether they would actually succeed at that institution.

Below-average standardized test scores do not equate to below-average intelligence. It just means that these students have a different way of thinking compared to other students. In fact, some studies have shown that high standardized test scores do not correlate to success in college; instead, they find high school grades are the best predictor of success at higher institutions.

Today, more and more colleges are getting rid of standardized test requirements on applications. Last year, the University of Chicago became test-optional and justified their decision as a means of “enhanc[ing] the accessibility of [the] undergraduate College for first-generation and low-income students.”

Today, over 1,000 colleges in the United States are test optional. This policy improves access to these schools for more students who would not normally apply simply because they feel constrained by their test scores. If the College wants to be truly need-blind and fulfill its goals of welcoming and including lower-income and first-generation college students to its ranks, it should become test optional or completely exclude standardized tests from its application.