*Content Warning:*

This article discusses mental health, self harm, depression, and suicide. If you are in distress, struggling and/or having self harm, depressive, or suicidal thoughts, there are both on- and off-campus resources available 24/7/365.

If you want on-campus help and need help right now, call 315–859–4340 and press option 2 to speak with a counselor from the Counseling Center. Confidential on-campus resources include the Counseling Center (call 315–859–4340 for immediate help or to schedule an appointment), the College Chaplain (315–859–4130) and the Health Center (315–859–4111).

If you want off-campus help, call 1–800–273-TALK or text “START” to 741–741.

*****************************************************************

When Natalie* entered her senior year at Hamilton College in 2018, she had everything mapped out.

As a double major, she immersed herself in her math thesis while writing a 70,000 word novel for her creative writing seminar. Post-graduation, she had her sights set on finding a copywriting job.

Although she was taking medication and seeing a therapist weekly at the Counseling Center, Natalie* had been struggling with thoughts of suicide for years. After spending a few months on a new medication that wasn’t working, she started to spiral.

When Natalie’s* roommate discovered her making plans to take her own life in their dark side dorm room, she reported her to the Dean of Students Office. By the following Monday morning, Natalie* found herself sitting in the office of Lorna Chase, who at the time was the Associate Dean of Students for Student Support.

At first, Dean Chase was concerned, but remained calm and sympathetic as she listened to Natalie* explain the situation. “It was obviously close enough to be scary,” Natalie* said to her. “But I didn’t try to kill myself.”

According to Natalie*, the meeting then took an abrupt turn. Dean Chase explained that she had called this meeting to determine whether or not Natalie’s* parents should be informed, and ultimately, whether or not she’d be required to take a leave of absence.

As soon as Dean Chase proposed the possibility of involuntary parental notification — and especially an involuntary leave of absence — Natalie* panicked.

“I knew I didn’t want to leave, but I felt helpless. In that moment, I felt things slipping out of my control,” she said.

While Natalie* had a good relationship with her parents, they weren’t involved with her treatment for mental illness. “I never talked with my parents about my issues. They didn’t understand the extent of it.”

In addition, she said that she knew that they had a tendency to be “overbearing,” and even controlling, in her life.

“I knew it was just going to make things worse,” she said.

While Dean Chase agreed that it would be best to not call Natalie’s* parents, she first stepped out of her office to consult with Jeff Landry, Vice President of Student Affairs. He allegedly informed the former dean that the parental notification was necessary — even if it was done without Natalie’s* consent.

Natalie* understood the consequences of her parents being notified. But she was even more terrified of what could come next: the possibility of being forced

to take

a leave of absence. And against the backdrop of working on her theses, she knew that a leave of absence would devastate her academic plans.

Leaving for a semester wouldn’t just throw Natalie* off track for graduation in 2019, but would also take her out of the two senior seminars that she said gave her excitement and purpose on the Hill. In her mind, redoing a semester would leave her isolated at home while her friends graduated without her.

“It would have been stifling,” she said. “The thought of being completely alone on a leave of absence at home, going back to school, and none of my friends being there was horrifying to me at the time.”

As soon as the possibility emerged that they could send her home without her consent, Natalie* said she started lying. “I decided then and there that I’m going to say whatever [they] wanted to hear.”

After Natalie* downplayed the severity of her depression and outlined the support system she had at Hamilton, Dean Chase ultimately dropped the idea of a leave of absence. But Natalie* was deeply frustrated that she felt she had to fight for the right to continue her education.

“I was completely at their mercy,” she said. “They were deciding what was best for me and all I could do was try to convince them to hear me out.”

Natalie’s* experience raises a critical question — for Hamilton College and for colleges across the country — about the rights and agency of undergraduate students who are still stepping into adulthood.

At the age of 18, many college students are often living on their own and making countless decisions for themselves. However, with a mental health crisis sweeping college campuses, what does this independence look like in practice?

Shifting policies on parental notification and leave of absences further complicate this notion of privacy and autonomy, especially in many colleges’ efforts to prevent student suicide.

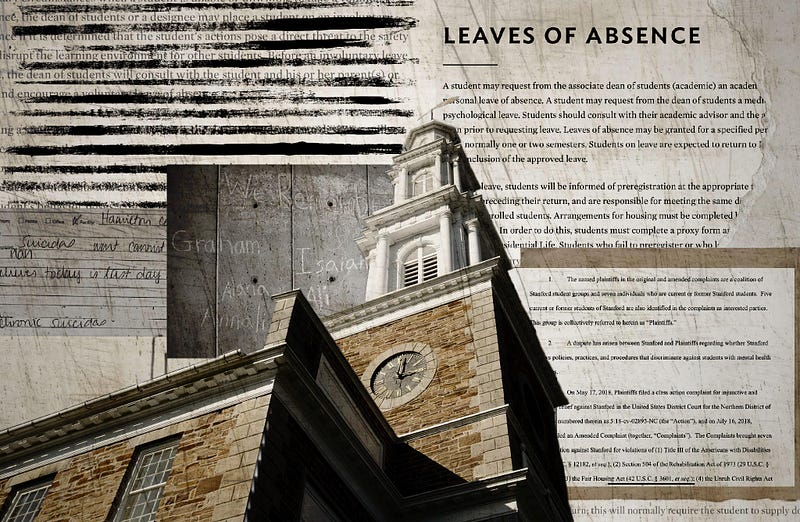

The Graham Burton Case

For Natalie*, this meeting with the Dean of Students was shocking, but it wasn’t unexpected. She sensed a mental health crisis building on campus for some time.

“It’s been boiling over for a while now,” she said. “After Graham Burton, there’s just been a lot of distrust in how the administration handles mental health.”

The Graham Burton case started as an on-campus tragedy, but soon unfolded into a controversy that would become a turning point for conversations about mental health and parental notification across the country.

In late 2016, Gina Burton lived through every parent’s worst nightmare: A child away from home, struggling in his classes, sinking deeper into depression. His parents were the last to know.

According to the New York Times, it wasn’t until two weeks after his death, when Mrs. Burton read through Graham’s diary, that she discovered the truth. Graham had been spiraling for months. He was failing many of his classes, barely sleeping and had a long list of absences and missed assignments.

Mrs. Burton

wrote a letter

to the Hamilton College community in April 2018, opening with a direct statement: “We do not believe the College has done enough in the wake of our son’s death to safeguard other students.”

In this letter, Burton addressed the question that left her searching for answers to begin with. Despite numerous warnings from professors and administrators, the Burtons had not been notified of Graham’s difficulties on campus.

Her open letter sparked new conversations on campus about how the administration handles mental health.

In the wake of Graham’s death, as well as another suicide in 2017, there was an external review that suggested several changes. The Counseling Center expanded their resources and hired new staff members. The Dean of Students Office hired Dean Lorna Chase, a licensed therapist tasked with assessing students with mental health concerns.

But in many ways, the damage had already been done. The campus community was stunned by the loss of multiple students, still grappling with the implications of the Burtons’ letter. At a town hall later that year, students yelled out, “Mental health on this campus is a joke” and “They [the administration] don’t want students on campus who have mental health concerns.”

The new Associate Dean of Students Lorna Chase sensed this tension as soon as she stepped into her role.

“There was palpable pain on this campus,” she said in an interview with

The Spectator

prior to her resignation. “I know that students were angry — I felt that I walked in and was the target of much of that anger.”

The Mental Health Crisis and College Liability

As youth suicide rates

climb across the nation

, colleges and universities face a unique challenge. They are charged with protecting students while also navigating a complex minefield of potential legal liabilities.

Suicide is the

second-leading cause of death

for college-age adults in the United States. And according to the

National College Health Assessment

, approximately 10% of students reported having serious thoughts of suicide in the past year and nearly 2% reported a suicide attempt.

In the face of such daunting statistics, college and university administrators and staff are working to protect the students in their care. Many students can see an on-campus therapist or clinician much faster than they can in their hometowns — and they may have additional access to emergency services like hotlines and EMTs.

However, academic institutions ultimately are just that — institutions of higher learning. Therefore, some critics believe these schools

may not be equipped

to offer the extensive mental health counseling required to meet the growing needs of their student body.

At Hamilton College, former Dean Chase understood this growing need all too well.

“Students know there’s a long wait to get into the Counseling Center,” she said. “The psychiatrists are fully booked at times.”

As a result of the rising number of student suicides on college campuses since the early 2000s, institutions have faced numerous lawsuits alleging that the school failed to do enough to protect its students.

A 2007 death at Virginia Tech led to a settlement requiring the university to notify parents of any warning signs that a student may be suicidal. A similar lawsuit at Cornell in 2011 led to the placement of additional barriers on the bridges around campus. But not all cases result in changes in college policy or culpability on behalf of the institution; M.I.T was found not responsible for a 2009 suicide.

While court cases have gone either way, the question of liability is complex and murky. Many students who are suicidal

may not “appear” depressed

, even in the days or hours leading up to their deaths.

In addition, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ model college officials can follow to determine what constitutes a risk of suicide. Students may experience suicide ideation, show signs of self-harm or even make a plan to commit while still stopping short of a suicide attempt. Others may attempt suicide without exhibiting any of these warning signs.

Roughly

12% of students

enrolled in the nation’s colleges or universities have reported experiencing suicidal ideation. Advocates like those from the Jed Foundation

say that it would be impractical, if not impossible, to provide emergency treatment or medical leave for every student who has a suicidal thought. They also argue that doing so would be unlikely to reduce potential on-campus suicides. Combined data from several studies suggests that the odds of a student who experiences suicidal ideation completing the act are

1,000 to 1

.

And even if a student is determined to be in crisis, it’s not always clear what to do next. Different colleges have adopted varying strategies: mental wellness check-ups, committees to discuss at-risk students, increased mental health resources and more flexible policies for parental notification or medical leaves.

Many administrators who are responsible for this delicate process are feeling pressure to do the right thing. At Hamilton College, former Dean Chase found herself at the forefront of a shifting landscape in mental health policies.

Every day came with new decisions — some of them, life or death. Before starting her work, she asked herself: “What’s the most likely to help the student and keep them safe? And that is what would allow me to sleep at night.”

Bringing Parents Into the Conversation

At the core of Gina Burton’s letter was a question echoed by many parents of students who have died by suicide: Why weren’t they notified that their child was in distress?

The

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) is

a federal law that governs the access to educational information and records. FERPA also allows for communication about a specific student among higher education staff, faculty and administrators who are concerned about the welfare of the student and have a legitimate educational interest.

But

when it comes to communication with off-campus individuals — including parents and family members — the law becomes more uncertain. Karen Bower, a lawyer specializing in mental health and disability discrimination in higher education, spoke to

The Spectator

about the legal framework of this issue. She calls the language of FERPA “permissive.”

“There are a lot of exceptions to confidentiality and ways that information might be shared,” she said.

Though

confidentiality obligations limit communication between campus professionals and others on- or off-campus, there are more than a dozen different exceptions, including any instances where students provide consent to break confidentiality, or if parents still claim the student on their taxes as a dependent. One factor overrides the others in every case: if a student poses a substantial risk of harm to self or others, school officials may

contact a parent or family member.

Due to the ambiguity surrounding the term “substantial risk,” this also leaves the decision primarily up to the judgment or discretion of school officials.

According to Associate Vice President of Student Affairs Jeff Landry, if a student is not a threat to themselves or others, the Office will only contact family with the student’s consent.

If they determine that a student may be a harm to themselves or another person, the policy becomes more flexible. “We will first work with the student to get immediate help. During this process, we will encourage the student to speak with their family,” he said in an email to

The Spectator.

“In cases where students are independent or have explicit instructions not to contact a parent, we would not contact the parent(s). In all other cases, we would work with the student to contact their parent(s). And if they choose not to, we would only contact the parent for help and support as a last resort. These are all case-by-case situations and we evaluate each case independently to determine the best course of action for the student.”

Dean Chase argued that involuntary communication with parents or family members is rare, and that most students can benefit from bringing parents into the conversation. Dr. John Dunkle, Senior Clinical Director of Higher Education at the Jed Foundation, agrees that

engaging families is critical.

“I’ve seen situations where parents are great partners in bridging the gap between students and the school,” he said. “It’s an opportunity for students and their families to make informed decisions about what to do next.”

However, if the threshold for parental notification is too low,

experts warn

that there could be consequences. For example, notification could make the situation worse in cases where the parents are abusive or uninformed on mental health issues.

In Natalie’s* case, she believed the decision to call her parents only created more problems for her at school.

“It’s usually a control issue for me,” she said. “My mom freaked out and started sending me texts asking how I was. And if I didn’t respond right away, she’d flood my phone with texts. I knew she was trying to help, but it just made me feel worse.”

Parental notification without a student’s consent isn’t unique to Hamilton College. In a 2016 resource document, the

American Psychiatric Association (APA)

warned against the “worrisome tendency to overreact to recent campus tragedies by weakening confidentiality requirements and even mandating parental notification. These changes could have unintended deleterious impacts on the care of college students.”

The APA argues further that parental notification should never be mandated,

even if

a student poses a substantial risk to themselves or others. Instead, their report recommended that “the nature of the student’s relationship with his or her parents needs to be explored and assessed prior to a decision about disclosure.”

The report specifies that these judgements should be made through “careful consideration in collaboration with the patient.”

However, Natalie* alleges that she was not given the option to be present for this phone conversation, which contradicts the policy presented by Dean Chase at the time.

Dean Chase described her typical notification procedure: “Students have choice over [the call]. Do they want to call first? Do they want me to call first alone? Do they want us to call together?”

In a later interview with

The Spectator

, Vice President and Dean of Students Terry Martinez confirmed that the Dean of Students Office would only speak to the parents without the student’s involvement if the student were “incapacitated,” or otherwise unable to make decisions for themselves.

When Natalie* later met with her psychiatrist and another staff member at the Counseling Center, she said the staff member expressed disapproval with Chase’s actions. She recalls them saying, “They should never have called your parents without you being a part of the conversation.”

Confidentiality, Privacy and Consent

When Natalie* sat across the table from former Dean Chase in the fall of 2018, she said she was presented with a form. It was a release form that, according to Chase, would allow the Dean of Students Office to legally receive information from the Counseling Center.

In addition to off-campus communication, FERPA guards students’ rights to confidentiality of records. If a student is seeing a therapist at the Counseling Center, for example, the Dean of Students Office can’t access information about what a student has said in therapy.

However, release forms like those presented to Natalie* would legally release that information to the Office.

Dean Martinez argues that this consent form can allow the case manager to better understand a student’s situation, as well as get a professional recommendation from experts at the Counseling Center. She adds that this communication of information would also “never occur without a student’s express written permission.”

Although Natalie* said she didn’t want to sign the form, she felt pressured to do so by Dean Chase.

“She made it sound like I was more likely to go home if I didn’t. That was the only reason I signed it. Because I just desperately didn’t want to go home,” she said.

When she returned to the Counseling Center for another appointment, she was again presented with the release form, this time by her therapist. As a boundary to protect student confidentiality, they said she would have to sign it again in the Counseling Center, with full consent, before they gave out any information. Due to the pressure placed on her by Dean Chase, Natalie* felt uncomfortable with them accessing her information, and she decided not to sign a second time.

However, in another incident, sophomore Cameron* reported feeling the same pressure to sign away his confidentiality rights in the Counseling Center. Back in spring of 2020, when he was struggling with thoughts of suicide, his on-campus therapist called him in for a meeting. She explained that she was worried for his well-being and didn’t want to release him.

When Cameron* swore that he wouldn’t “do anything stupid,” he alleged that his therapist told him: “The Dean of Students is not going to want to me to let you leave until you sign this form.”

He decided then that he needed to leave, even at the expense of his right to privacy and confidentiality.

“In that moment, I just wanted to get out of there,” he said. “And now, looking back on it, I feel like a lot of the information I shared was really personal. I don’t want the Dean of Students to have that information.”

“It’s Time For You to Go Home”

While Natalie* described the parental notification without her consent as “uncomfortable,” it was the prospect of an involuntary leave of absence that truly shook her to the core.

Some students who are struggling with mental health, including those experiencing suicidal thoughts or ideation, may take a

leave of absence

, or a medical leave. For many students, a leave of absence allows them to take a break from the stress and pressure of higher education. While at home, they can focus on recovery as they prepare to return to on-campus life. This leave can be for one semester, a full year, or, in rare cases, an indefinite leave.

“It’s the first time, probably since grammar school, students are given permission to just take a break,” said Vice President and Dean of Students Terry Martinez, describing Hamilton’s current flexible leave of absence policy. “That’s a hard thing for some students who are wired for success and constant work. For students who take leave of absences, they come back and they can graduate.”

According to the Dean of Students Office, the vast majority of these cases are considered voluntary. In the three years that Dean Chase was employed at Hamilton College, she could only recall a few cases where a student was sent on an involuntary leave of absence. The current Associate Dean of Students for Student Support, Dean Sarah Solomon, claims to never have encountered an involuntary leave during her two semester tenure at the College.

After tragedies on other campuses, some schools have turned to a more open-ended leave policy. While schools argue this increased flexibility lowers the barrier to allow students to seek off-campus support, some students allege that these policies are too vague, and that they allow room for situations where a student may be sent home without their input or consent.

The result is a trail of devastated students who claim that, after turning to their college for help, they were ripped away from their campus lives and forced on a leave of absence that they didn’t feel was necessary, or in some cases, was even more damaging to their mental health.

Stanford University settled a landmark case in 2018 where seven students alleged that they were coerced into taking a leave of absence. Other legal challenges against institutions like

Princeton University

,

Hunter College

,

Yale University

,

Ohio University

and

George Washington University

accuse these universities of discriminating against students with mental health issues instead of offering on-campus support to meet their needs.

Even as colleges work to destigmatize mental health and offer more resources to protect students, leave of absence policies remain a controversial issue on many campuses. The implementation of Hamilton’s own involuntary leave policy has left some students feeling mishandled or even abandoned by the administration.

When Cameron* expressed serious thoughts of suicide to his therapist from the Counseling Center in fall of 2020, she told him he needed to go to the hospital. That morning, campus safety officers escorted him to St. Elizabeth’s, where he reported experiencing a traumatizing series of events. He said he spent eight hours in a concrete room with no access to food and faced verbal harassment from nurses on staff. Later during his stay, he said he was groped by another patient, which was not recorded in his medical record.

The only thing that kept him going during the long hours of his four-day stay — many of which he spent coloring with a single broken crayon or watching the hands on the clock tick at a snail’s pace — was the thought of getting out, going back to campus,

and returning to a semblance of normalcy again.

When he was contacted by the school the day after he was admitted, it was his therapist from the Counseling Center, who told him that they had a plan to send him home after he was discharged from the hospital.

“This is what the Dean of Students Office decided,” he recalls her saying. “It’s best for you to go home.”

He made it clear that he was not asked for his input in this decision about taking a leave and neither were his parents. “They didn’t get any verbal consent from me. They just told me ‘it’s time for you to go home.’”

During Cameron’s* hospitalization, staff from the Dean of Students Office allegedly exchanged flight information with his parents. They booked his father a plane ticket to pick him up and take him home.

While these conversations about his future were happening without him, Cameron* described feeling “helpless.” Although he felt stable enough to return to school at the time and feared the consequences of being sent home, it was clear that the decision had already been made.

After being discharged late on a Monday night, Cameron* was sent home for the remainder of the semester. As part of their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Office allowed Cameron* to transition to remote learning, where he could continue his classes virtually.

While he says he considers his removal from campus to be involuntary, Dean Solomon, who was assigned to his case at the time, denies that she ever encountered a situation where a student had to be sent home without their consent.

Another Hamilton College student who chose to remain anonymous reported a similar encounter with the administration during their hospitalization. The decision was reportedly made by the Dean of Students Office without any input from the student or the parents. While both argued that a leave of absence wasn’t necessary, the Office offered no opportunities for appeal.

According to the student, their flight home was booked for them while they were still hospitalized at a local psychiatric ward.

A fourth student who spoke to

The Spectator

under the condition of anonymity outlined a similar situation. After experiencing what she describes as a “major episode” on campus, she says she was sent off campus without her consent. The school informed her parents that she would have to leave campus and take a medical leave.

Looking back at the situation now, the student believes that leaving school was the right choice. However, she was left feeling “shame and betrayal” at the way her case was handled without her input and consent.

“I’m ultimately glad that I was able to get the necessary help and treatment that I needed,” she said. “But the process itself was traumatizing — I didn’t know what was happening and I had zero information communicated to me by the school itself. It was as if I didn’t exist. In their minds, I was no longer a student, but a potentially dangerous person who also happened to live on campus.”

After Cameron’s* discharge, he wasn’t allowed to set foot on campus to collect his items or meet with anyone from the Dean of Students Office. Instead, he was immediately sent back to his father’s hotel room before heading to Syracuse airport for their flight home.

As soon as Cameron* went home, he says his situation took a turn for the worse. Facing a tumultuous home life and abusive behavior from his parents, taking a leave of absence had serious consequences for his mental health. He alleged that his parents immediately turned the blame on him, thinking that he “was the problem.” They yelled at him repeatedly about his hospitalization and surveilled him closely in everything he did.

“They saw me as a ticking time bomb and they were just waiting for me to nuke,” he said.

As a result of this, his mental health spiraled. Cameron* credits his strong relationship with his friends and another sibling as his lifeline during this time. If he didn’t have them, he says he would have been “sucked to the bottom of the ocean.”

Upon further reflection, Cameron* says he wishes he was given the chance to discuss a plan that would have allowed him to stay on campus, including appropriate accommodations like speaking to professors about deadlines or working with his therapist on a recovery plan.

Mental health in higher education lawyer

Karen Bower agrees that accommodations are at the core of legal issues surrounding leave of absences.

“Regardless of whether there’s a supportive family or not, the leave policies have to provide for reasonable accommodations and look at all options for helping the student before imposing an involuntary leave. In fact, a lot of the recent cases have been explicit about that — they have to try every measure they can to allow the student to stay and succeed before placing them on leave,” said Bower.

Bower points towards the

Mental Health & Wellness Coalition v. Stanford case

as an example of what these accommodations could look like in practice. This class action challenged Stanford’s leave of absence policies, arguing that their practices “discriminated against students who were at risk of self-harm due to a mental health disability.”

The parties agreed to settle the case, and the resulting settlement established a rewritten

Involuntary Leave of Absence and Return Policy

, as well as the hiring of staff specifically trained to ensure that students have the right to consider reasonable accommodations that might enable them to continue their education, avoiding a leave of absence altogether.

For Cameron* and the two unnamed students at Hamilton College, they felt that this right to reasonable accommodations wasn’t upheld.

If a student is an immediate disruption or danger, Bower says that schools can act immediately. However, she states that the student still needs to be made aware of their right to appeal and allowed the opportunity for due process, including the right to present evidence.

“There still has to be an appeal period. Even just the minimum of an opportunity to provide information with the option of a more extensive appeal process later on,”

she said.

All three students also allege that they were not offered an opportunity to appeal the decision of the school. Two students were sent home immediately upon discharge from the hospital — they reported no mention of an appeals process — and the third student reported that she was not contacted by the school after being sent home.

“It Made Me Feel Like I Wasn’t Welcome Here”

As noted by college administrators and other experts, the statistics are clear. Cases of involuntary family notification or forced leave of absences are rare.

But it doesn’t erase the reality that students across the country have experienced another side of their administration’s mental health policies — one that left them in the dark about their futures and eroded their trust in school officials.

These stories may not make up the majority of leave of absence cases, but they can have a lasting impact.

Due to the fear of being sent home — or of not being readmitted after taking a leave — these policies may discourage students from coming forward for help. And it won’t help if students see the administration as a barrier to mental health support instead of a resource.

Unfortunately, this is exactly what happened with Natalie* back in 2019.

“I felt that I wasn’t their first priority,” she said. “I thought they had the best interests of the College in mind. So I didn’t trust them. I didn’t want anything to do with them after that.”

After being sent home, another student said that this experience changed the way she viewed Hamilton’s commitment to mental health, to the point where she knew she could never go back.

“I’m not willing to put myself in a position where my psychiatric condition precedes who I am as a person,” she said. “Empathy and accommodations are only mandated in situations that save face and uphold the narrative of Hamilton’s ‘inclusive’ environment. Otherwise, it is better to quietly usher an individual off campus. Their commitment to mental wellness and health is performative, at best.”

Cameron* echoed this sentiment, saying that he felt like he had lost his trust in Hamilton.

“It all comes back to liability,” he said. “It made me feel like they would rather have me kill myself off-campus than on-campus. It made me feel like I wasn’t welcome here.”

After his traumatizing experience in the hospital and the emotional scars left after his semester at home, Cameron* fears what might happen if he contacts the school for help again.

“I feel like I can’t speak out anymore,” he said. “I wouldn’t trust the school because of what happened to me. I’d call my friends and hope that they could get me out of it — I’d take that chance rather than taking the risk of being too honest with the school again.”

Accountability, Transparency and Advocacy

The involuntary leave of absence policy outlined on Hamilton College’s website can be found under the

College Catalogue

.

The policy reads,

“Before an involuntary leave is considered, the dean of students will consult with the student and his or her parent(s) or guardian(s) and encourage a voluntary leave of absence.”

When considering an involuntary leave, administrators follow a multi-step process. “Prior to placing a student on an involuntary leave, the dean of students or a designee will meet with the student and explain the reasons why it is under consideration. The student will have an opportunity to respond.” In addition, the dean may include assessments from campus officials or health care professionals to make an “informed decision.”

In all cases, according to the current campus policy, “reasonable accommodations that would mitigate the need for an involuntary leave will be considered.” While the dean or designee may take immediate action to place a student on involuntary leave if they pose a direct threat or disruption to other students, they state that they will provide the student with “an opportunity to respond to the action in a reasonable period of time.”

The policy articulates several points that Karen Bower J.D. highlighted as critical for upholding student rights, like consulting the student about their leave of absence, offering them a chance to respond and considering all reasonable accommodations. However, the policy makes no mention of an appeals process.

Dean Martinez points towards a more informal appeals process, in which a student would have to personally reach out to her via email to request an appeal. She confirmed that this process was “not articulated in the policy.”

Dean Martinez also stresses that the Dean of Students Office takes careful consideration of a student’s background and needs when considering an involuntary leave.

“Everybody has different circumstances,” she said. “It depends on what home is like for some students and their access to support. It depends on how disruptive the student is in our community. It depends on whether or not we provide the level of care that is required and recommended.”

Unlike some colleges and universities facing lawsuits from students, Hamilton College claims to not operate under a “blanket” policy. They argue that each student’s individual circumstances and needs are assessed before taking drastic measures such as a forced leave of absence.

However, students maintain that it’s important to consider how closely Hamilton adheres to its own policies, as well as how this might impact the lives of students.

Bower points out that this discrepancy could put the school at risk. “It’s one thing to have a policy,” she said. “But it’s another to follow this policy. If they’re not giving the student an opportunity to challenge the decision to place them on leave — if they’re not getting an appeal — then they may be violating student rights.”

To address student concerns about transparency, Dean Solomon told

The Spectator

that she plans to implement a website with a more comprehensive version of the policy, as well as a clearly outlined process for pursuing a leave of absence and returning to campus afterward.

“One of the things we’re working on is making it really transparent for students how that process works and making it as easy as possible,” she said.

Dr. Dunkle agrees that transparency is a critical part of the process. He also argues that students should be given a voice in the process of developing policy, especially when the future of their education is on the line.

“I always encourage engaging students as much as possible and allowing them to have input on some of the policies. Clearly articulate them to the community — what they are, why they’re in place. That would hopefully grow more confidence in the administration,” he said.

Bower also poses several concrete solutions that the College could consider to address these student experiences.

For students who are struggling

,

but aren’t immediately at risk, Bower suggests a system where students have the opportunity their freshman year to determine who they would like to be contacted in case of a mental health emergency. Students with difficult home lives or who would prefer a parent not be contacted can determine an alternative contact, including another family member, a guardian or a friend.

In emergency cases where students

are

at risk, she again stresses the importance of reasonable accommodations and “minimal procedural safeguards that allow for some kind of due process,” including “an opportunity to be heard and present your side of the story, present documents or additional information, and an opportunity to appeal.”

This process should also include the student’s own input. “Not only should they be talking to the student, but the student should have an opportunity to give their side and to provide information from their parents or treatment providers if they want,” she said.

The Stanford settlement, which led to a more thorough and clearly outlined involuntary leave of absence policy, can also act as a model for other schools to follow. Many of the changes made to Stanford’s policies offer safeguards to ensure that student rights are protected and upheld.

For students like Cameron*, Stanford’s new policy includes an option for students in unsafe situations — with difficult home lives or unstable backgrounds — to remain in on-campus housing while receiving treatment.

The settlement also ruled that, “Stanford shall ensure that its Office of Accessible Education (OAE) maintains sufficient staffing and capacity such that staff members with expertise and training in working with students with mental health disabilities are available to assist students in considering possible reasonable accommodations that may allow students to avoid taking a leave of absence.”

In addition, the settlement required that a resource person who is familiar with the policies but outside the decision process in a given student’s case should be made available by Stanford to advise the student on their options, whether considering a leave or returning from a leave.

Some students agreed that having a staff member outside the Dean of Students Office to oversee the process would make them feel more comfortable advocating for their own rights.

Natalie* said that a third-party expert in the room would have helped her feel secure.

“It would have been nice to have an outside observer to see the conversation and make sure that my rights weren’t being violated,” she said.

Moving Forward: “Cut Through the Fear”

David Walden, Director of the Counseling Center, agrees that it’s necessary to address the harm students have reported experiencing, especially if they feel that current mental health protocols failed them during a sensitive time.

However, he argues that communities shouldn’t get too wrapped up in questions of blame.

“We can’t risk forgetting that everyone, really, is experiencing the same thing,” he said. “As a clinician, when I hear about these situations, I hear fear. Fear on the part of all of us. All of this is everybody being worried about something — bad things happening, somebody getting hurt. And everyone involved is trying to do the right thing. The caring and loving thing. And sometimes it’s really hard to know what that is.”

There may be no clear solution — no easy roadmap for colleges to follow. But Walden believes that an effective mental health policy requires schools to manage the anxieties that emerge from these complex and ambiguous situations.

“Sit with the tension, really sit with it. And that’s an incredibly hard thing to do in these situations. The only real antidote is using these strategies — individualized assessment, transparency and careful, methodical thought — to cut through the fear and the challenges.”